- Home

- Cisco, Michael

Celebrant Page 8

Celebrant Read online

Page 8

Silent, watchful, nervous, staring, but without a pigeon’s hollow inexpressiveness. Even a chicken is capable of some show of distress, but a pigeon, like an insect, has nothing but velocity to speak with; in a panic, the pigeon’s face is as blank and stupid as it is in repose. They look at every thing in the world with hapless alarm, a startled eye—What? What? The girls bend at the waist darting out a hand to the ground in an approximation of pecking the earth, to pluck up a coin or a raisin or a bit of string, sometimes a little mob of them all darting and picking at once in a spot where rubbish has been discarded.

These musty little girls have the same fits of abrupt scratching; and turn in unison to stare fixedly at any alarming thing with the same flick of the head; the same dipping bow of head in greeting another who comes to sit down; the same sameness that makes one like another; the same way of being there for so long and then gone. But they also turn their heads with imperial slowness more like an eagle’s, and they can play together, when they feel safe enough, with hard-won gaiety. There they are, sitting spaced out on the edge of a roof, picking their noses. Like rabbit girls, they don’t eat meat, and get their food by theft, snatching life a morsel at a time from carts, refuse heaps, the ground.

*

Rabbit girls fountain up over the open top of the cart snatching cabbages and carrots and dashing off with their spoils between their teeth.

They congregate in back of the stores, where a number of alleyways meet; crawling in and out of basement windows and along the ground, chattering in small groups and climb all over each other giggling.

Kunty wears a dirty, faded dress of indifferent color with shoulder straps, the shredded skirt hanging in long strips from her waist. She’s lolling on the broad side of an overturned barrel, her head lying on her outstretched arm, while with the other she absently scrapes designs into the wood with her nails. A few other girls trickle in from a drain pipe.

There’s pigeon girls over by the park (a newcomer says, apropos of nothing)

Those girls are inappropriate (Kunty says) Those girls are implausible.

She rubs her bottom pensively.

Those girls are ignoramuses (she says)

One girl with huge black irises, sitting nearby, says: They’re just plain stupid.

This is Ester, who cleaves to Kunty, praising and flattering.

*

A naked rabbit girl slides out of an alleyway wide-eyed—Hey! Pigeons’re stealing our tomatoes!

Kunty rears up, shaking herself vigorously, then streaks past the girl with a whuff of air.

A few streets away a grey girl with a beak drawn on her face in flaking silver paste brazenly steals a can of sardines in plain view of the vendor, inside his store. In the few moments he wastes chasing her down the street, pigeon girls spiral by the stalls in front of his shop swiping at a heap of tomatoes under a tarp.

They rendezvous with their spoils in a tiny lot where two brick buildings angle apart. Murmurs, smell of tomatoes.

Kunty erupts among them like a cannonball; they scatter. Some can feel the clout like breath, and hear the low whipping sound her hands make as she slashes just short of their fleeing backs and legs. They leap up to the eaves or bound through the windows to escape her, she raking with her nails a few of the slower and less fortunate, who cry out. Darting this and that way, attacking at will any who are near, excited to fury, Kunty suddenly pounces on a light-haired girl in dirty grey leotard, knocking her on her back and coming down on top of her.

The girl holds off Kunty’s claws, hands and feet, with both her hands and legs. Kunty’s face lunges out of her mop of hair and snaps, straining forward to bite. The strength of the girl underneath ebbs, her limbs slacken jerkily—then she rams Kunty in the gut with one knee, and releasing Kunty’s arms, slams her across the face with her open hand, knocking Kunty aside, slip out from under her. Kunty is surprised, but she ripostes at once, lunging forward to be met by another crack across the face in exactly the same spot as the first and so quickly she can’t see it coming. With a shout she swings toward the movement and is struck twice more, slaps in the face with a little hand so fierce that it twists her head—see stars. There’s the other girl winding up, the light behind her—moving first she shoots forward nails out and that hand bangs her down, once again hitting her precisely in the same place. Kunty staggers a little and the other lifts her two hands and claps Kunty’s ears between them with a splat. Kunty’s legs jerk and she jumps back with a loud cry, holding her sensitive ears. She buckles back onto her ass, then pivots and scrambles away, stops about halfway down the alley, still rubbing her ears, hissing with pain and confusion.

Run Burn! (a window shouts)

and, after a moment’s hesitation, looking after Kunty whose gasping is already reverting to snarls of rage, the girl in the grey leotard bounds up the wall and away.

Still wobbly, Kunty rushes back, crouches, and jumps up the wall. Hanging by her hands—she sees they’re gone.

*

Pigeon girls gather on a pitched roof top, squat down huddled with their backs to the wind, all keeping fairly close to a warm chimney. The news travelled rapidly among them—

Burn beat up Kunty!

The exclamation in each case followed at once by—

Which one is Burn?

She goes by that name, having no other, and no one to name her. She’d just slipped in among them some day, from the upper city, from the other side of the boundary.

Gathered around, pigeon girls quietly ask her, with pointing hands, again and again, to show them how she did it. Patiently, Burn re-enacts the fight with scrupulous exactness, a series of postures without rage fear or the flaring excitement already becoming a dance, conjures the phantom of Kunty in the hollows of her own body’s motions, every time striking the same mark in the air with her hand.

If you watch pigeons (she says) The way they move their wings. They move their wings like.

She brings her raised hands down and together—pop! Looks at them for signs of understanding.

They look at her. All of them are looking at her. In the distance, she sees a huge black bird turning circles over the city, between her and the mountains, collapsing into a virtually invisible black line as it comes toward her, then tipping to the side and huge again, like a pair of black swords, toward her, away, toward her again.

deKlend:

On his third day at the Daubeb Xafif Madrasa, deKlend awakens to the sight of an enormous man looming over him. His seamed face is hard to read from this position; he gives the impression of being at once severe and impassive. deKlend starts violently, both in surprise and with a spasm of the leg caused by a weird feeling, like the muscles had just been given a speculative squeeze by a ghostly hand.

Who are you supposed to be? (the security guard asks him flatly, as if deKlend were in costume)

I’m faculty (deKlend lies) New faculty, actually.

The security guard looks very displeased.

Well I’m on the faculty myself, actually, and I’m not aware of our having the use or money for anyone else here just now. What are you doing here in the first place?

For someone as dismally real as the security guard, his questions, his voice, are like a prolongation of deKlend’s unrelated dreams.

That’s a good question (he says yawning and thrusting his head back deeper into the seat cushion)

Isn’t it, though? (the guard says, leaning forward irritated) How about an answer?

deKlend blinks at him innocently.

Well?

...I suppose it started with that dream I had...

deKlend describes his dream, taking special pains to detail the characteristics of the strange figure he had seen, hoping perhaps that this guard might, if he knows anything on the subject, condescend to enlighten him. He knew that it was Friday, and yet he felt as though it were Sunday.

What are you talking about? Explain yourself.

I am explaining (deKlend says patiently) You a

sked me the cause of, or reason for, my being here, and I say that it was the veiled man who sent me, more or less.

The security guard recoils.

Veiled man? (he asks sharply) Describe him.

As he does so, the security guard begins shaking his head slowly, interrupting him to ask,

Did he ever change into a bird?

Oh yes. Funny sort of bird, too.

With long ears?

Yes that’s right! But it wasn’t an owl—(deKlend yawns)

When he reopens his eyes—and he can’t say for certain that his eyes had been open before—there’s nothing above him but air and ceiling. The room is vacant, except for him. The dawn within the window is brown, and deKlend sits up miserably, rubbing his head. His jaws ache; he’d slept with them clenched.

Ah, how stupid I was, (he thinks) to think I could get to Votu from here! All this while I’ve believed this was a part of—part of what?

He blunders into an ordinary room and finds there a sort of packaged meal with complicated instructions printed on it. Ignoring them, he begins manipulating and damaging the package, eventually mashing it completely out of shape. It bursts open, scattering dry, long-spoiled food on the floor. Not a crumb remains in the package, on inspection.

Two men pass the door.

They were just a buncha fakers (the first one says)

They always are (the other interjects)

That’s okay (the first replies)

Thinking duelling thoughts to and fro like jammed logs piling up against the rocks—pound, crash, the logs fly like thunderbolts, bars not of light but soundrod batonning the ground of the banks of the river, logs batonning the drumheaded earthbanks rockslimed bankrocks slimheaded fish bolt weave a little light in logbath morass or flip sunengaged in reeking mud soft as slime banks waterlogged earth tails of silver drum in final batonspasms alternating with the head against the logs, fish in slim bark grooves by banks all smiling with woven slime glistening in the sun, gills hard on grooved bark and fins grappling among blonde splinters silver dappled in beaded plaits of water rill down log flanks to the flickering stream’s groin where the batonbrooks defile rocks, the log sleeps in creamy slime mired in silver from splintered clouds, a blonde halo of white bark suffuses the bank, where the logs rot, crumbling in phosphorescent decay that decals the fish scales, logs soften on the banks and become witty gleaming fish, escape me like girls into the curling glass of the stream.

Overcome by the feeling that I don’t want to do anything, only lie back and dissolve into the homeless clouds and rain I came from. I was put out (he thinks). Out of sorts. Everything I had to do seemed to be an inexplicable formality, although I can’t say who expected it of me or why. I wracked my brains and couldn’t imagine, even imagine, a future that could connect with the stagnativeness of my circumstances.

Was that really true, or did it only seem true? I felt as if something in me had jammed, so that whatever happened, good or bad, came to me in the same defeated way, overcasting even my pleasant thoughts—without anticipation, they seemed like things that had already happened—life just happened.

For as long as I choose to remember, I have been called intelligent (he thinks). What’s intelligence? A stupid idea. And what meaning were they giving it, in applying it to me? Naturally I didn’t disagree with them, and found myself meanwhile time and again doing stupid things, knowing all along and often even beforehand that they were stupid and yet blithely proceeding to do them anyway, even knowing all along that I did care whether or not I was doing something stupid, or at least, cared whether anyone whose opinion mattered observed me doing it. I knew all along that what I was doing was stupid, and did it anyway, so what use was it to me to know that when knowing it didn’t stop me? How “intelligent” is that? And what do I make now of all the smart things that I didn’t do, knowing they were smart? Or of those occasions when I did refrain from doing something because I thought it was stupid, and then turned back and back again afterwards in pure befuddlement, or trepidation, so that, even when I received word that some other imbecile had blundered headlong into the pitfall I’d managed to avoid, I could take from my indecisive decision no satisfaction.

There can be no mistake (deKlend thinks) I am an idiot.

Assured of this, he believes he has just established himself more firmly on solid ground than before.

But certain thoughts, I mean certain kinds of thoughts, come in clearly (he thinks), even too closely, and this is precisely because I don’t invent them. They come from beyond. Without reservation, I put my trust in dreams, and what I call visions, although the word seems pompous, and other thoughts that seem arbitrarily solid. Like anything you would encounter, solid first, reasons, if any, attached later, like balloons or sprigs of flowers. But it’s thinking that makes solid things arbitrary—a persistent habit of mind that spontaneously, instantly proliferates anything that has the misfortune to come under its consideration, multiplying that thing by all the things that it is not but might as well be, flocking it, making it dubious, draining it of any decisiveness. Seethingly real thoughts blast themselves into my mind with crackling immediacy; these are always fakes.

Sometimes the idea comes in... not even clear (he thinks), but plain. Abiding just on the far boundary of calm, of silence. A tranquil, mute suspense, like looking at a painting. The command comes as the spell breaks, and, snapping back glimpsing something in my own complexion that had been drawn out with my elongation, and that shows me what I might do. That I should do what I might is obvious. What will you do? You will do something, that much is sure, and dignity has its being in that. The command may be arbitrary, but only from an outside point of view; from my point of view, as its homeless recipient, it is not arbitrary, because it is for me necessarily to make it the future, like a fate distinct from duty, even from duty for its own sake; although there is a resemblance, in this case the content of the command matters, because it is delivered into the present from the future by me.

The momentum added to me by the dream of the dark figure in the snow seems to have dissipated, and now I am marooned in this run down school. What now?

I look up and see motes in the beacon of muddy daylight that sweeps across the narrow hall, through the open doorway. I sit on a cracked leather seat with splayed metal arms, in a sort of glorified closet. The motes begin to exhibit an unmistakeable significance, portending what I don’t know—they seem to describe tiny vortices... They don’t actually spin, but they rise and fall, and some, the longer ones, which are like fibres in among the motes, I can see will sometimes make a single, abrupt rotation, like the acceleration of a leaf floating downstream as it slips over a hump of water bulging over a barely submerged stone. Pacific feeling. I watch expectantly, to see the greater order emerge. Resist the temptation to make metaphors. Just watch.

deKlend leaves his seat and enters the hall, going to stand beside the hay-colored beam. He gazes down across it, his face aglow in its secondary light. The bright motes are reflected in his black eyes. Inside and out, the silence is total. The motes rise and fall. His breathing is shallow, so as not to disturb them.

Hours pass. The beam does not leave its place. The unwaned light glints on the motes, tepid sparks. There are bright filaments mixed in with the flickering soil.

Abruptly, deKlend strides through the beam and the doorway facing him, the motes dancing in his wake, the light winks out. He makes his way down into the basement, to where some motheaten rugs lie in a heap. He squats beside them on his toes and, leaning over his knees, begins sifting the pile.

After a short time he gets straight up and makes his way from the basement to the tiny infirmary, which has glass cased cabinets and metal trays, a venex snakebite kit, and round bottles with their content labels etched into them. He opens drawers of chiming steel instruments flicking them with his fingers then snatches up a pair of needle-tipped tweezers. He returns to the basement at once and recommences his search at the beginning. Sifting the pile,

he draws each thread apart with a semicircular motion of the tweezers, checking every single one and then furling the rugs aside like flabby ledger pages. Each one emits a dense smoke of dust and lint when it lands.

More hours go by. It is dark outside. The basement now looks as if it were full of wafting incense. Cold sweat cuts grooves in the filmy webbing that clings to deKlend’s face. He is slow and methodical, unhurriedly checking every fibre, but his eyes are starting to bulge and get glassy—he has not shifted position once since he arrived.

Light is gathering again when deKlend completes the last rug. He gets up at once and staggers crazily on stiff knees but doggedly, up the stairs and down the hall to a wooden planter filled with turfed velvet. He kneels beside it and begins again to scrutinize each thread with a semicircular scanning movement of the tweezers. The nap of this pad is dense, and the day is well advanced when he moves to the collection of sheepskins on the back of the sofa in one of the store rooms. From there he heads to the attic.

He passes a mirror hanging above a nightstand in between two rows of lockers and stares at his reflection. He begins to tremble, and gingerly raises his hand to his mouth.

There it is!

The dim gleam of the bright filament, caught in his moustache. Watching the mirror, he grabs at it jerkily, and it escapes, retreating deeper into his moustache—no! He just turns his head in time to see it blink in a shaft of daylight gushing from a window in the hall to his right. deKlend dashes after it—it blinks at him again from the next shaft in the row of beams boring into the gloom of the corridor, and now the next, a tiny wink of gold turning in the clear air. Around the corner—gone—there in that sunbeam, it winks! Not far away—he swats the air like a cat, trying to drive it into a corner with the puffs, blowing out his cheeks.

With a loud cry of dismay he next catches sight of it placidly rotating out of sight in a doorway leading outside. There is no wind—there, he sees it, floating with the imperceptible breeze, and, from time to time, unhurriedly fluorescing as its shining flank turns toward the light again.

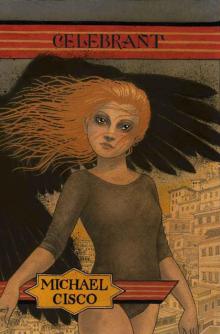

Celebrant

Celebrant