- Home

- Cisco, Michael

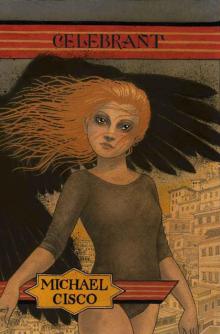

Celebrant

Celebrant Read online

Celebrant

Not ready yet!

Just a moment!

All right—‘just a moment’ (it says here)—ahem

I bid my mind welcome, along every unstained slab of the wide, never-used sidewalk, past the silent tract houses and down immaculate, unused streets, heading out toward the long red butte with pale flanks, into the wind and the purple hills. There over the fields I can see a huge black bird rising in the air; it turns and as it comes toward me or swings away from me it flattens and becomes invisible. I want to remember the necessity of its flight, and that necessity is easy; so I store these things away in my mind, which is the mind at hand. There is a mind, and thinking, but my confidence fails me when I try to call it my mind. Nor do I see any reason to consider it his. So it doesn’t matter who I am. I am a refrain of a larger music, all of which I don’t entirely hear myself.

The clay road gleams silver in the bright grey glare from the clouds.

I am the hallucination of a homeless man named deKlend; he does not know this, because I don’t appear to him. I’m a hallucination so I seem more than I am, and I’m always good company. If there are any indifferent or boring hallucinations, I’ve never heard of any.

Now there is light on the ground but the air is dim. I feel that the ocean is off to my right, although there is nothing but land. It may be only an unmoored feeling of spaciousness.

How do I look on land? At the land I mean. It isn’t a landscape or a scene, it’s the land—how do I look at it? And, seeing how unprofoundly profound and unsilently silent it is, and its utter innocence of meaning, how do I open my mouth and try to talk to it, let alone for it? There’s no way. So, since I must speak, I will speak for myself to no one in particular, and I will listen to nature. I don’t like the words “shaman” or “spirit.” I won’t use them any more. I’ll wait for words I can say, and they might even turn out to be the same words, uttered in a different spirit. And let there be halting ceremonial conversation only—absolutely no “natural dialogue.” Let every word be announced as though a child were reciting it laboriously from a book.

There are trees over there. Open land before me. No path and no grass. Bare clay. To my left there is a sprawling cemetery. As I pass it by, snow comes floating out of the doors of the mausoleums, from beneath the eaves of canopies of carved stone, and from the gestures of the statues and parts of the their stone bodies. The luminousness trembles and elastic fronds of snow steal around me. Not one flake touches my so-called face. The cemetery rolls like the ocean. The mausoleums, statues, headstones, ascend and descend in place just like swells on the sea, in the mute white swarm of the snow.

Entering the world on this occasion, I’ll make a brief, silent address.

The World: the world goes on forever, the horizon rolls back forever, the earth never rounds into a globe. Travel on and on, you’ll never come back to where you started from, which is not to say that your journey changes you or the time that your journey takes allows for great changes so that your point of departure will, on your return (having travelled for so long in the same direction and coming around the world) be unrecognizeable to you. It’s to say that there’s always going to be more and the idea that the world was a single limited globe turns out to be a wildly unlikely mistake. No one has ever seen it or mapped it, and you can go on from land to land follow one after another without end. The exploration begins inside your own body. The world I’m exploring is familiar, the oldest I know, but I so seldom try to put into words what it’s like. People are creatures, among many other kinds, who haunt it. We speak in murmurs or cries, but there’s no conversation or clothes, cities. People die because they remain where they are, so perhaps eternal life is travel is forgetting. Limits, it might be, are precisely what make travelling and forgetting, and consequently immortality, possible, because those limits are also what prevent me from ever reaching the end of the world forever and ever, ahem.

The Journey: he has to go perform the rite in a pilgrimage destination, and he’s one of many. The others will know him and he them, that’s for certain although he can’t bring any particular sign to mind any more than he can clearly recall being set the task in the first place (there should be a memory) in part to prove that the world, while it is a globe, is nevertheless infinite, and geographers and map makers have made a mistake. Perennially novel experiences in nonstop travel are the only proof possible of that. Travelling beyond the horizon, you will never come back again—you will go on and on, the world forever accompanying you—in companyless company—while space does extend to infinity on all sides, and this is a small planet, but nevertheless a mistake has been made, a bizarrely common mistake, in thinking that the voyage will not continue forever discovering unfamiliar countries and landscapes, seascapes, animals, plants, people of course. There is a mystery in back of it, having to do with other dimensions, that is not troubled by any of the contradictions in these ideas. I’m not troubled by them or by my confusion; I just let it alone and move on forever and ever, ahem.

All around I can hear the banshees, their wails shrill above the blue, the curse of unrequital belching from their hooded heads flung back, groping for hallucinations with fingers indistinguishable from the wind, calling for me but without knowing my name.

deKlend they know. He is so alone that even his own hallucination is estranged from him. I come from him and I don’t know him; he’s like an overcast spot that emits images. You see him, but then, as you draw near, images come spiralling out of him and carry you away. Denial has bestowed extraordinary powers on him; every thing that’s in him is excommunicated the moment it arises, and comes back to him in time like an encounter in the unreal exile of permanent solitude. I have seen him taken aback a few times; I think he must have realized, in those moments, how far he’d journeyed away from everyone else already, and how much he’d forgotten and replaced with images.

The silver gleams of the puddles and the wet clay ground are relentless. They are relentless. They are relentnesslessly restlentless there’s that empty tree in thickening snow, my going on is like lying down because like the snow I don’t feel myself falling.

Finally I am asleep.

Now I am sleeping, with my sleep all around me, my own placeholder only seeming to wait in the midst of it, just having just parted, united instead to copious sleep. Shadows of sleep play on my form... I see it plainly, all naked as I am, and idiotic. Remember that, he is an idiot. Sleep playing too close on my idiot homeless hallucinationbody, I can’t say where, but I watch over him.

Something seems to crash into his chest and he doubles up with a moan of pain and horror. Powerful blows crash down on his chest—a hammering beak breaking it open, thrusting in between ribs. He sees his ribs like rafters overhead. The ragged opening there, and the blind, staring black bird’s head jabs through, beak snipping the flailing heart. He is hauled out of bed by his hair. Dragged along by his hair. Cloth is slapping his face making it impossible to see. He twists his neck. He sees a head at the end of a long arm, an enormous, silk-hatted, caped man veiled from head to foot. The head swivels and turns its invisible gaze on him. The floor shakes with each of his swift steps in a kitchen—heavy blows crash into his chest, so that he bounces wildly on the mattress. Now overlapping hands press him down with immense strength like stone rams massaging his already beating heart. Blood knocks in his head, buzzing in his ears, his feet throb, the feeling makes him despair. In one wheeling movement he is sent sprawling into a corner as the giant draws up his stool and sits, feet apart, in the middle of the kitchen. Leaning forward with elbows on knees he clasps hands together, extending index fingers together and thumbs folded over them. IT lowers the stylus of those two fingers slowly, cutting into the air. Gelatinous air-shavings plop around it

s feet like clear rubber rags. The air spins like a potter’s wheel and IT is cutting a hole in space, spreading waves and sickening discolorations through space and him, bunching in membranous ridges and congealings—

IT seizes him by his neck and drags him through the aperture, plunging him in dim, transparent beams, like rays of smoke, and shocking cold.

Again he glimpses the veiled head, and two insane glints. The hat he now sees is a Chinese scholar’s hat with the two wings. The wind is scathing, veils and black broadcloth mutter furiously around his head. What is there to see but ice, black fabric jerking in the wind? And now some bird, flying just ahead, black and intermittent in shreds of flying snow. That bird is huge, with long ears on its head, and wide, daggerlike wings. The grip on his head is gone and he alone is struggling to contain his panic and get his bearings, whatever those are.

There’s a groove here between frozen, stone-solid snow drifts. He can go only forward—preceded by that bird, whose passage opens the only way for him and pulls him on like an ox hauling a plough. The wind batters him so he rolls with its gusts, feeling his body lunge this way and that—but he knows he’ll freeze on the spot if he stops moving.

The path narrows ahead. Hanging motionless in the air with wings outstretched, the bird leers insanely back at him—it has a wolfish muzzle instead of a beak. Hot acrid air bursts over him and there, just ahead, orange fire gushes on white snow. The wind lapses suddenly and he staggers as its force leaves him, gaping at bulbs of impossibly brilliant orange, like blown glass, swelling from this white snow. They collapse in plumes of howling steam. It’s lava, or no it’s metal, bursting in gobs from the rock like a hot spring.

A shadow engulfs him, and he feels sick. A rough hand spins him around and all the strength abandons him. With a feeble cry he is flung naked into the fire.

Will it happen? That is the idea. But this is an opportune moment—the dim sun has just departed behind the horizon, and now the only illumination is a shower of tiny meteors slanting down through the trees. The shadows of trunks and branches slide like criss-crossing screens, as though the trees were silently rushing around in all directions. He can sense he is missed in the dark and confusion. He is eluding him. He is eluding...

Celebrant

by Michael Cisco

Chômu Press

Celebrant

by Michael Cisco

Published by Chômu Press, MMXII

Celebrant copyright © Michael Cisco 2012

The right of Michael Cisco to be identified as Author of this

Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published in June 2012 by Chômu Press.

by arrangement with the author.

All rights reserved by the author.

First Kindle Edition

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Design and layout by: Bigeyebrow and Chômu Press

Cover art by Christopher Conn Askew

E-mail: [email protected]

Internet: chomupress.com

To Robert Parker and Karen Kahler.

Contents

Celebrant

About the Author

Celebrant

deKlend:

As for me, I don’t dream, I am dream, and I can’t look down and get a clear look at the process that brings me about from moment to moment. That’s deKlend over there. I am here, and... he’s there.

Imagine approaching a park bench, up on your right. You crouch down not far from one end of the bench. deKlend appears on the bench, one leg casually thrown over the other. It’s raining. His right hand rests on his right thigh, and holds upright his capacitous umbrella. The left elbow is cocked onto the back of the bench and a long, elegant left hand hangs in space. The head and shoulders are nearly lost in the crosshatched shadow beneath the umbrella. The rain falls straight to the ground, and the umbrella makes a column of rainless air. He sits with his head tilted back a little, wearing an expression of self-satisfaction, although he might simply be enjoying himself.

deKlend is the type certain positions give rise to, or he likes to think he is, imagining he came into being like the figure between the shapes of a mobile. An optical illusion, like the vase with two faces confronting each other, one day happens to twist in the breeze and there he is, with feline self-complaisance licking his hand and smoothing down his eyebrows and moustache. No embarrassing memories. No shameful home.

He has a somnolent milk white oval face, and large circular eyes like liquid coal under heavy lids. A black muffler of fine lamb’s wool is wound round and round his neck, and he keeps the ends tucked into his jacket sleeves. This makes his neck seem longer, and causes him to tilt his chin up.

He might be seen sitting on a park bench in Union Square or on the Author’s Walk too close to a fine romantic drizzle, his right ankle across his left knee and his left elbow resting on the back, drawing the sleeve of his jacket, the exposed cuff glows white in the gloom beneath his umbrella. He does absolutely nothing, but seems ready at any moment to pop up onto his feet and deliver a sheaf of fluorescent papers to a bureau. At the moment he simply broadcasts his gaze, holding the long loose fingers of his beautiful left hand slightly extended; the nails only look dirty—actually there are fingernail hyphens printed there in ink at the rim of the pink crescent.

He can be found going to and fro in the street with an attache case or a portfolio or loose papers or documents he’s had to vaccinate with his own signature. deKlend is strictly a go-between; he never originates anything. Even when he originates something, he does it as his own go-between. He conceals a principle in everything he does, and it’s not his fault if people are too stupid to see it; all his images strictly adhere to the hidden pattern in the hidden centers, but, as I say, he is his own go-between, and is no more to be found in those hidden centers than anywhere else. I suspect he went from folly and shame to dignity and shame, and since he is already somewhere toward middle age, from there he became furious, sweet, wistful, and resigned. With a ruthlessness that is often shockingly like downright stupidity he returns to images of the sky, the weather, the landscape. These are his Gorgon-turning shields. Clouds, the sky, the air, its smell, the trees, the horizon.

He spends all his time thinking. He shuns desks and often conducts his affairs, whatever they are, sitting beneath a table in a lot stacked with domestic furniture—wardrobes, sideboards, bookshelves, nightstands, hatstands, a great many wooden hampers and bins, all in rows many tens of feet high. He climbs under a table that happens to be standing on its legs, on the ground, as part of the bottom layer of one of these gigantic stacks, and writes, setting the papers down on the black, sticky ground before him and curling forward with his shoulders between his knees. While there, he savors the smell of cut lumber and varnish, and the smouldering aroma of old springs and stuffing of the upholstered furniture stored inside the warehouse. Often he stares with glazed eyes at the underside of the table’s far corner, which is braced with a crosspiece to form a triangle all bunioned and corned with brown glue that oozed from the joints and congealed lacquer.

Hopeful people with things to sell make use of the alleyway, which runs perpendicular to the wind and so is one of the few places where it is bearable to stand outside for any long period of time. The period is necessarily long since practically no one has any money to spend, less and less, and what money does get spent is spent on food. This means that the ones who want to sell books, clothes, household odds and ends, must offer food as well. A basket of puny, dried up potatoes, or a little jar of pickled plums, chocolate powder compressed into a cylinder and wrapped in newspaper. There’s no shortage of food, but it goes elsewhere. Having found, to his complete astonishment, a coin in the return slot of a

pay phone, deKlend has come to the alleyway with the idea of buying something to eat. Immediately next to a tangle of rusted plumbing there is a bare table with three broken, weatherbeaten pies on it, and he makes for them at once. The man vending them also has a few dirty cardboard boxes packed with books, and some of them have been hastily slopped onto the table next to the pies. This man only missed being tall; there’s a shawl of undyed wool draped over his head and it dangles along his corduroy lapels like the ends of a judge’s wig. He watches deKlend without getting up from the high stool he sits on, with a blazing little clay stove just in front of his feet. Taking deKlend’s black coin with a brisk turn of his puffy hand he gestures to the books haphazardly stacked by the pies.

Go on and take one (he says) if you like.

There’s no charge? (deKlend asks)

Go on (the former replies) They’re not worth my carrying them around any more.

As often happens when he examines lists or rows of books or other labelled or titled things, he looks too closely, is immediately confused, and fails to take much of anything in. This makes close perusal necessary, and what feels like a great deal of needless effort. But presently he chances to select one of them and so takes possession of it.

On examination, this book presents itself as a geographical encyclopedia, surveying a great many different countries. The authors, whose names are not prominently displayed anywhere in its numerous pages, but only intercalated with the material in the undemonstrative way one would expect from a genuine encyclopedia, invented these countries and their peoples and customs by modelling them on familiar ones, mixing traits, modifying some, reorganizing large social shapes, such as monarchies, often by tracing the ramifications of a very minor change. The article that deKlend finds most interesting describes Votu, a country on a high plateau surrounded by gargantuan mountains. The entry goes on for over a hundred pages, and the writers even went to the trouble of supplying a great many photographs. Some show people who seemed to be very cleverly made up, or they might come from somewhere west of the Roseate Lamina. Although there are no mountains like those in that direction to the best of his knowledge, which is small. This imaginary country is stuffed with monasteries, each one built around a small library of precious texts which, far from being very old, are at the same time premature and as old as or older than the orders themselves, because they came from the future, and have yet to be written. These books, spelled b-o-o-k-s, are called books (pronounced like “flukes”), to distinguish them from books (like “hooks”). It is an invarying tenet of these monastic sects that books are not sent from the future with any deliberation or addressed to the past in any way, they simply happen to appear. Time, they say, only seems to have a single direction; in fact, time runs in all directions, which is another way of saying it just runs, period, and disciples who have achieved the highest state of mental skillfulness are able not only clearly to conceive of this abstruse idea, but even to observe time’s emission or scintillation on a grand scale, ocularly. Books are borne back into the present from the future in what is vaguely described as a kind of ambient current. They can be read, and naturally the mathetes pore over them, but their sanctity has less to do with their content, which is as diverse as any chance sample of books, although not all mathetes are convinced that the content is diverse by chance, or even diverse at all. Regardless of and above the question of opinion with respect to content, the books are sacred because, in reading them, one is reading words that exist in the present as words that will be written, and not copied, since these are the original words. They will be written, and that means there is an invocation, a summoning note, that calls from them. Their content ultimately comes down to what answers, more than anything else about them. The mathetes read the books, whatever their other reasons might be, in order to remain within their call and be near to what is to come.

Celebrant

Celebrant