- Home

- Cisco, Michael

Celebrant Page 2

Celebrant Read online

Page 2

*

deKlend also has the dream—the kitchen, the snow, the fire, the heavy-footed man, wakes with a bleat of alarm and sits up, swinging his feet down from the bench. What are they saying? Some broken thoughts—Rubbing his face, he tries to draw the dream out.

Is it the dream, or is it a story that all too quickly takes up the images of the dream and makes sense where none had been? Meteors fall in the wood.

A fierce black bird with long ears and a snout, with hands instead of talons; a sardonic wild man in a veil. “Mnemosem,” a misread word, that might have come from the book—it might have been a heading at the top of a page, and not a complete word. It follows him like a leitmotif repeating in his mind and not distinct; whenever he stops, his attention settles decisively on it, yet does not firmly grasp it. It’s a word, he thinks, that almost means something else, like an approximate synonym or a modification. He believes it has nothing to do really with memory. It doesn’t mean a rememberer, or a rerememberer, but it might mean someone who memorizes but never remembers or reremembers what is memorized. Memorizing to forget. An equivalent discipline of forgetting. Do these make sense or are they just waves, like a wave of the branches, passing over and making a stir but without changing anything?

deKlend begins walking.

It had the vividness of the presentiment (deKlend thinks) the arbitrary quality, but then I’ve only read about presentiments, haven’t I? There was the time I dreamt of her together with—no, not him, but with someone I didn’t know but who might have been him, as well as anyone. It’s a summons—or no, it’s not. Yes it is! It’s the call I must have been waiting for, at last!

deKlend draws out the book again and begins to flip through it. Here’s a photograph of a sizeable black bird standing in stubbly ground, taken from a distance. Nothing else to see in it. “Bird of Ill Omen,” the caption reads.

He’s always believed that he thought that he was going to be called to deliver something, a confidential message, important communique, a gift or prize, answer, or something of the kind, and it would begin with a call particularly addressed to him. Only he would, only he could, recognize it as the call. Who would call, he had assumed he would have known, but that the call should come like this was never ruled out, since nothing at all had been ruled one way or the other about it. The call was supposed to leave no relevant question unanswered, which means that, if this is a call, then therefore in its bareness, and in the riddling baroque imagery that attended it, it must have answered all relevant questions.

After all, what questions would I ask? Do any questions matter? That the dream should appear in my head indicates that I and not someone else is chosen. It is plainly from outside my head that it comes, because I can’t account for the apparition of such intense and bizarre experiences by the usual means. Could it originate in some quarter inimical to me and bent on luring me to my destruction? Come now! Anyone capable of projecting dreams could have found a more alluring one than that, but what if an alluring dream was ruled out as obvious entrapment?

I repeat that anyone capable of projecting dreams is capable of destroying me at a distance already. And if this is a game, then I should rise to the bait and outsmart my enemy. How do I know that this supposed enemy did not count, for that matter, on my thinking myself cagey, so that I would trap myself in not rising to the bait?

But there is no enemy (he thinks) Who would want to hurt me, or I should say, who would bother to go to such lengths to hurt me, when I have done nothing nearly as elaborate to anyone dead or alive? As I reason on the subject, I find myself more and more confirmed in my suspicion that it was a call—the call.

He picks up the book again and peers at the waxy photographs, still headily perfumed with developer. To go there, no doubt (he thinks) I should find myself—

In Votu:

In Votu, time is commonly supposed to run backward. It is insisted, however vaguely, that, everywhere else, what exists is understood to protrude from the past into the present. In Votu, what exists is understood to protrude from the future into the present. Time pours out in a stream whose current goes toward the past, although their preferred metaphor for this is a burning incense stick: the past is ashes, still retaining the shape of the stick for a time, then dispersing to dust, while the future is unground leaves, and the present is the ring of fire.

Votu is reached by crossing a high steppe plateau of long green grass. Like a glacier, the city flows from an inaccessible source high in the mountains, and extends down onto the plain. A boundary separates the piedmont zone from the upper city, and, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, nobody lives above the boundary. Looking up, the people of Votu watch as the future city arrives, having already existed from time immemorial and thus being older than the city they’ve come to know, sliding inexorably down the slope and piling up on top of them. People move into the new buildings and adapt to the new streets as they cross the boundary into the habitable zone, while the older structures opposite are driven down and crushed together, collapsing to form a sort of rubbery scrim at the city’s lowest extremity. The compacted past city forms a dense integument, not unlike a callous, that makes the erection of an outer wall unnecessary along that side.

Those who, crossing the boundary, ascend into the future city find empty, still, expectant streets and houses, over which huge sculpted heads preside. These are expertly carved in stone, with such subtle command of expression that there can be no mistake the faces are meant to be seen as sleeping, not dead. They are all different. Some faces are composed, others sprawl. The air there is tense, and the buildings are much overgrown, but there is very little animal life. The populated area of Votu echoes with birdsong from end to end, and the birds are always first into the new sections, but they don’t go far into the future.

People don’t venture over the boundary into the future area because it, like the rest of the higher mountains, belongs to what the natives call forgetting-country. Forgetting-country is under a natural spell that makes certain forms of remembering fatal. No one who goes there dies for having remembered how to tie a shoelace; that kind of memory is as harmless there as anywhere. Likewise, familiarity, as someone eats breakfast, as someone catches a glimpse of the view from bed—that variety of memory does not trigger the spell. But memories of events, parents, names, specifics, can’t be safely brought to mind beyond the boundary. Every recollection of such things contributes to a morbid condition resembling chronic arsenic poisoning. Unfortunately, the killing influence also comes into play whenever one remembers that it is unsafe to remember things, building up in the softening brain of the victim until paralysis, coma, and melting. Remembering others who have died in this way is the most toxic of all forms of memory. Anyone who remembers a victim is virtually certain to become a victim himself.

The boundary is part of a prophylactic scheme laboriously put together over many years by specialists, forgotten and written down. There are no barriers, just signs that are visible only from the lower side, so as not to remind anyone who dares venture above the boundary. The cordon is lined with lodges occupied by municipal hypnotists who are sworn to entrance and de-memorize all who seek to pass beyond.

deKlend:

deKlend is sitting in a restaurant when the colors suddenly become more distinct as if someone had adjusted the lighting—

—oh no—

They become more distinct and his lips grow cold—

—oh no not here—

The food he’s chewing loses all its flavor and he shudders and becomes sick—

—someone is listening in on me, is anyone attending to me, is someone paying attention to me? Someone is reading me!

Starting, his arms jerk stiffly and his plate cascades to the floor. Attention picks him out like an unseen spotlight—swallowing his half-chewed food is like forcing down a handful of nails. A diamond-shaped crack of light twists shut around the flowers in a plain, trembling little white carafe—

Someone is writ

ing about me! Someone is reading me! Who? Who?

In the night outside an owl answers him, the flowers bounce after the plate, and if it wasnt’ for thei for that pety paesky hammer knoickiong his thoughts apar t the rain has stopped outside like it never happened—sick clammy white page which one who’s reading me gleatinous sickly cold black ink—the lon graggedd sniff like tearing paper, the waiter looking odwn at him—flares up like guttters like a canalde then flares up again gutters flares guuterres flares sof ic andtyjt ek ci tn the darkjnd disgutsing sight of the food half smeared on the palte I mean the clioth the water in the glass vile water—too close I’m being fascinated—soesome’s attention ois throwing off my delciate machinery—I’ve fall into favor—no—I’m bein favord—I’m being favored/faxinated—

deKlend keels over backwards kicking out his legs and hits the floor rigid as a plank, his moustache bristling around his bared teeth, the features seem to melt and alter, his eyes turn to moons, a grating, hawking sound in his throat, like harsh laughter. He’s having the dream again—

...When the attack passes he clambers up from the floor holding his pounding head. The fits usually allow for these deceptive returns, and he knows he is liable to fall again at any moment.

His body feels light and empty like a ghostly afterbirth trailing from his thousand-pound head. A second skull is trying to break its way out of his own smaller head. His clothes are twisted; they bind his legs and arms. The table is on its side. The diners are quiet and many have actually pressed themselves against the walls, murmuring, staring. Someone is shouting something in the back. He hurries outside, half fainting, and groping before him with his hands, into unrefreshing night air that buzzes intolerably in his jaw—a punch knots and spreads in his gut and his mouth floods with brine. He pitches helplessly onto the gravel on all fours vomiting, with brutally long pauses between each spasm.

Staring with stupefied eyes at the gravel just ahead of the gradually augmenting splatter, where a circle of light cast by the restaurant shines past him, touching the short fringe of colorless grass.

The grass is the dawn rim of the world. Many miles below him is the dark velvety basin of the earth. Above him is the deeper, clarified darkness of space, and distance is the only thing between the stars and him. Soaring in this thin, air-like medium his wings hang suspended without adjustment.

deKlend is a bright, cold mist.

He looks out into space, into a weirdly nonuniform darkness made of overlaid meniscuses of blue that soften and blur together in a broad crescent in front of him. Into that blue-black space erupt the sun and horizon at once, crashing into space in a single spinning wave. He gasps. Tears roll down his cheeks. Sweat bursts from his skin. He lists forward as though he were praying. The unbearable intensity of the vision increases.

He is buoyantly tossing on the wind, so high above the surface of the earth that even with the sun’s full effulgence beneath him the sky above him is luminous black. Now he plunges steeply from that immense height into the earth screwing his fingers into the soil, knitting them into the crabgrass he forces his brow hard into the dirt and his whole body trembles even as he plummets from on high like a javelin. Below him, black and white mountains raise their spines above a green steppe that ripples in bands of reflected scintillation like ribbons of sea froth. The mountains are blackened teeth in a dead, livid jaw. The back of deKlend’s neck contracts violently snapping up his glassy-eyed face. Shivering uncontrollably he streaks like a meteor just above the tops of the long grass, the insanely distinct peaks of the mountains gnaw the horizon ahead and before them rises the outline of a city, surrounded by a foaming surf of trees. deKlend leaps up and takes off, running down the dirt road that leads away from the restaurant into the luminous country of night, the road lined with flame-like trees that imperfectly screen the shimmering, clabbered fields of pleached blue paste. Sluicing gusts of air cross his wings carrying him on to the city like a shot. Unable really to turn his head he can only crane his eyes upward toward a silhouette melting against the sun now high above him. It’s a bird, and he is its shadow. Streets and buildings suddenly rush up and engulf him. His shadow form folds, stretches and contracts over irregular surfaces of streets and buildings, not seeing the buildings except as frail transparencies—but vividly seeing the people.

Like fish in a reef, they zip in and out of doors, criss-crossing the streets, making way for each other, they clasp hands coming together or apart, they speak to each other, they meet, they welcome each other. They welcome in a threatening, endearing I’m more secure in not being understood than in being understood, in not understanding or needing to understand what makes people tick what am I a cop? In Votu dignity isn’t a luxury the crowds aren’t just faceless human porridge, each face here is specified, each face is dignified with a special activity, special to it.

The towers and domes of the city shout rapturously against the sky. Men and women and children built this choiring self-monumenting life-form, present all around him, called Votu who knows why? His mouth frets out the syllables of the name in another body. He whips forward over scalps and hats in avenues thronged with people, passing over palpitating fountains of brilliant water effulgent with reflected glare. Then, in the cool side lanes, where a fine grey-blue shade is sifted like ashes to the earth, there is an eddying stream, just here, of little girls in rags. His speed increases, his legs are wings. He is hurtling down the bird’s road. The girls jet into the crowds and lace themselves in among the other people as fast as little fish schooling. These quick, homeless little girls shine like silver, flashing in the daylight. deKlend leaps. He jumps. He leaps again. deKlend disappears—the night road is empty.

The bus is enormous and might be a train car. It plunges through the night, and deKlend half-deflatedly sits against one of the huge windows on the right side, in a corner. Outside, whirling by barely a few feet away from his face, are gnarled, sawtoothed black rocks jumbled in heaving surf—the water glows deeply cobalt blue vividly contrasted with incandescent white foam that flips and spurts webs of hissing lace over the rocks. Washed with spray, the track is canted toward the water so that deKlend is nearly looking down into it. Although he never takes his eyes away, he knows that, through the windows across the aisle, he would be able to see a similarly jagged blue-black collar of shrubs against a weirdly brilliant overcast sky, and beyond that, the yawn of a vast blackened continent dotted with ancient settlements and alien cities.

The car is lit pell mell and people from all nations sit mostly by themselves. A woman with skin the ashy color of undyed linen, and long slender eyes, is sitting across the aisle in a seat facing the other way. Her black hair is cropped very short, salted with grey, and she nestles her drawn, tapering face into an ebullient, shaggy wool collar. deKlend is neither talking to her nor remembering an earlier conversation, but it’s as though simply imagining her, and attributing to her in imagination a few aspects of speaking, like a certain limp way of gesturing with her skinny hand, were enough to connect the two of them.

Now they’ve stalled—or rather a bus has stalled and all the traffic is stopped and has been for a while. People have gotten out of their cars and are walking unhurriedly forward. Some of them gather to jump, fists in the air, from the overpass down onto the road below. Someone must have told him about the stalled bus. He can’t see it from here.

deKlend feels eager anticipation and a kind of predisposition to find things profound, as though he were about to meet the love of his life. These others have, like him, decoded something distributed to the world in some unremarkable disguise, a crossword puzzle or a contest or something, and, following the directions they decoded, have thus found themselves all together this way. At the great house, gathered quietly, like old friends and even more like former lovers who meet again for the first time after years and years, they’re talking quietly with each other. He’s talking with that woman, who reclines on a sofa, her eyes watch the nearly colorless flames rushing silently on th

e hearth. She calls the purpose of their search “alchemical” and he wonders what she means. All this mulling over of clues and possible meanings isn’t as irritating as he would have expected, because it’s a game.

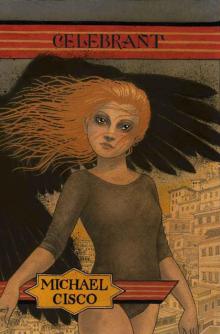

Celebrant

Celebrant