- Home

- Cisco, Michael

Celebrant Page 3

Celebrant Read online

Page 3

But don’t you think (the woman says) that the point was to bring certain people together like this, and that the destination or discovery waiting for us (is thought or said) is secondary in importance to our being collected, or to what we do together?

She asks him about himself. He tells her, but his story seems unreal, as if he were inventing it all. Being a boy, going to school, his father and mother—he remembers it all, minutely, and none of those abundant particulars are decisive. They all could just as readily be something else. His father might have been boisterous and brawling. His mother might have been mournful and wailing. He might mistake her story for his, and listening for telling, although that’s a drastic mistake to suspect yourself of making. The important thing is that he is an unmoored, homeless man. Does that mean he can set forth on his journey easily, without preliminaries? It’s closer to the truth to say that he is completely within his limitations and travelling constantly. To have reached such an age without successfully putting down a single root could almost be considered an accomplishment; and there are seeds discovered in ancient tombs that are just as prone to sprout as any others. A seed is neither alive nor dead, it waits to live.

Looking out into the complete dark, putting out a hand to feel his way along, in that dark it’s not unlike the pale shoot that breaks from the seed and reaches out homelessly for sustaining dirt. That is, for night soil. The usefulness brings it around again. There is a particular bit of ground that deKlend wants—

In Votu:

In Votu, the people circulate constantly in areas, even at night. People in Votu are often hard to see, they blend in with the buildings so well that they seem to appear out of walls. You see the exaggerated speed of the walkers near you flashing by, and the equally exaggerated slowness with which distant people float along. Nevertheless the people are by far more conspicuous than the architecture. The people, not the buildings, are the city. The buildings would simply rise up around them as they circulated in place, almost as automatically as the heaps of sand feet push up walking on a beach.

Coming into Votu during the day there is an odd sound, part of the general whirr of the city, a unique sound with a familiar quality that inevitably makes the hearer think of an audience of applauding giants. The people you see in the street rarely follow the pavement, most of them are darting to and fro across the street in short trips from one door to another, and the sound of applause is really only this incessant clapping of doors, shutters, manholes and hatchways. A city of doors and brush-bys where the streets are so crowded in places that people are noodling in and out among each other brushing by with breathless, soft expressions of excuse, pardon, and apology.

It’s a city for walkers; one only occasionally sees bicycles or horses pulling carts. The pedestrians of Votu are quiet, polite, and don’t smell bad, and walking like this is sort of fun. After a few dozen minutes of jaunty bumping I find I can’t take myself entirely seriously. I look up a sloping street at a kaleidoscope of heads flashing against a white square of sky. Door open, emerge, close. Rush to the next door. Open, disappear, close. It’s the fussiness of bothering with the doors, rather than just leaving them off, that seems so funny. Doormakers do serious business in Votu; the typical wooden door has a lifespan of perhaps a half a year. The doors I see are thin, curling at the edges and semitransparent with wear in the middle. Knobs and latches are usually dangling loose or falling off, if there is anything but a round hole there. The doormakers keep coming up with new, more durable designs, which are received with minimal enthusiasm. You constantly see cheery doormen screwing new doors in place or removing old ones, and special angular wheelbarrows for conveying doors.

There are no streetlights. At night, everyone carries a little lamp or phosphorescent object. Looking out from my balcony at dusk, after a long and exhausting journey, the city is like a firefly hive. Glide along lights, stop and start lights, bounce up and down lights, zip in and out lights, stately slow lights, groups of laughing face lights, two shadow heads together and the lights held well out at arms’ length, lights held up to faces with livid eyes shouting at each other.

The houses, though, blaze with an especially clear light that is generously allowed to escape through open shutters onto the street. Some streets make me think of wandering around the outside of a brilliantly-lit mansion, although in this case the “mansion” is just a collection of individual houses.

Going down a sloping side street, a door flips open in front of me and a man steps out, lifting his hand and quietly asking my pardon. I’ve dropped my light and lose it. It went out. As I turn round and round looking for it, in the street behind me I hear a ringing sound. There is a shadow there, at the corner below me. A hooded figure, or it might be a veil. A shade half-congealed from the night, it sways, and takes a step, scraping along the wall. Then stops. I hear it breathing hoarsely. The head seems to be looking without moving much, like a drunk’s. I hear the faint tinkling sound of a bell. The bell is attached to the ankle of this sleepwalker, to warn people to stay out of his way.

*

Ontacagan, a building in the middle of a short lane that connects two other streets like the crossbar of capital A, is the focal point of current religious practices in Votu. The facade opposite it towers overhead, while the adjacent buildings are only slightly taller than it is. The one to the left is a hollow shell filled with its own rubble, the one to the right is an ordinary shuttered house, a two-storey box, where the caretaker customarily lives. Ontacagan itself has a red tile roof and immaculately scrubbed white front. Black Radio stands on a dais inside it, against the rear wall. It is a primevally large bakelite console with one round speaker, two scalloped knobs, and a crystal panel like a wafer of pure, frigid blackness of interstellar space. It’s so black that no one can see the numbers, the fine ruling of the spectrum, the tuning wand. The operator finds the signal by listening, and dead reckoning. It both receives and sends signal, so it is possible to tune into it with other radios if one knows where to look. Its signal, they say, is omnipresent.

Black Radio is always on, and its static can be heard all along the length of the lane and, in the quiet of the night, through the walls, along the plumbings. It sounds like insects, hissing and rustling somewhere, and at times it becomes a more continuous whooshing noise, like a tide shifting on a shoreless ocean. On auspicious days, Black Radio utters something—a low, flat, faint, crackling, warped voice that barely emerges from the static can sometimes be heard. The voices sometimes speak in chords that swell and ebb. It usually mutters unintelligibly to itself for some time, and it may be that there are continuous transmissions too faint to hear. The decipherable content often takes the imperative mood. Black Radio has been heard to scream, in a woman’s voice, or to shout with stunning power and annihilating authority.

The caretakers use water calculators to come up with increasingly precise tuning schedules. Votu is like a colossal ear, and, in this metaphor, Black Radio is the auditory canal drawing signal down to the drum, the earth. This is why, from the self-centered point of view of the citizens, Votu produces the best leaders and musicians, who really know how to listen. Speculating about Black Radio and the origins of the broadcasts only it can receive is a pretty common pastime. They are said to come from the legendary Land of Hybrid Emotions—hove and late, pear and fride, jealleity, despage.

One of its first officially-registered messages was: no the... no a. This was interpreted by the listeners to mean that articles, definite or indefinite, should not to be applied to holy things, which is why no one ever refers to it as the [etc], but only... Black Radio. One speaks of the natural robots, but the article is never attached to their nicknames. Was it a commandment, with implicit penalties? Opinions vary, but most take it only as a suggestion, or more accurately as an experiment in tact, to see what sort of effect the elision of the articles might have.

Types of messages from Black Radio:

(listing)

person knife power again

mouth enclose earth sunset big female son inch young work tiny bow heart dagger hand sun moon wood water fire field eye show fine-silk ear clothing speech cowry-shell walk foot metal door short-tailed-bird show eat horse one two three four five

(recitating)

to no sound but birdsong

to no sound but birdsong

(eavesdropping)

b-but we need a new cetagovy, a whole other axe (?)

tue many minicos around her...

the dragging outline like a steel mosaiche,

I don’t like anything...

(singing)

spirits of the night and day

come flit away this mel-o-dy

(children’s voices)

Your hair is cold!

Must be special water.

Your hair is cold! Your hair is cold!

I want my hair sprayed!

I bet you did it backwards.

I’m not talking about it! It’s kinda... It’s kinda...

Put your head in there.

No, because you’re going to turn it on!

Does this thing work? I don’t think this thing works.

I wish I never split my lip because I don’t want that scar.

Scars are permanent.

deKlend:

They’re petals. They’re flames. They’re solitary fingers. They’re shining coins. They’re white candies. In a whirlpool, too close to the blackness of space. Creation unrestrained by any scheme and unchanneled to any profit, making into something else every thing he sees.

A solitary farm house, two storeys tall, remains of a small barn behind it. The barn has collapsed, timbers still half-webbed with shingles sticking out, a crushed straw hat. One dead tree by the house. The air is still here, and as deKlend approaches, stillness thickens, a pool of silence around the house. His feet make a hollow scraping noise on the porch; his knock is dull and faint. He’s travelled a long way already.

The windows have no curtains, permitting him to see the plain room inside. His breathing echoes against the front of the house. The little cold brass knob, which would have been less out of place on an interior door, turns and the door flies open crashing against the wall with an explosive clatter as the lock and bolt fall out and apart, leaving him with the knob in his hand.

The ruptured silence seals over again instantly, swallowing the racket so quickly and completely it already seems unreal. Setting the knob down, deKlend enters the house and gently draws the door to behind him. The floorboards give a few sharp pops and he unconsciously shifts to the carpets. An impulse to call out arises and vanishes. With an abrupt sigh he touches his brow and sways. Wearily he begins to climb the stairs as though he were home, thinking only of a bed. Cold, still air, dust, varnish, meaty wallpaper, glue.

Thin, colorless light at the upper landing, branches cross the window. Like a hand, a sound stops him—an even hum, steady as a note played on an organ, not low not high... He opens a door and the hum is greater there, not louder just greater. Bedstead in the corner, bureau with mirror over it, a few other sticks of furniture; the hum is coming from a bottle of amber fluid standing by itself on the bureau. It is the only living thing in the house, vibrating with that hum.

Half-raising his hand to it, deKlend hesitates; then he lowers his hand and goes back down the stairs, and out of the house. He shambles back toward the road, blinking back tears of frustration but he couldn’t just go to sleep in there, not with that hum.

He comes to a stop ten feet before the side of the road. Head down, arms at sides.

He turns around and goes back to the house, up into it and up the stairs. But now there are two bottles.

Like a huge piece of snowy lard, mottled with disease, dry suffocating heat—a terrifying red color—every now and then the pattern stirs deliberately—and then he begins to glimpse the nerve animals—a little sloth the size of a house cat, woven out of brittle, strawlike nerves, pawing lightly at the fronds in the wallpaper—

In the dark room with the humming bottles, the gleam in his eye remains when he vanishes without leaving. Sitting there, the spell gathers around him in curling waves of white petals, snow, but that’s somewhere else, not in the room. The flakes of light are the two windows with the curtains drawn aside like hips, revealing nothing, just two silver panes like mirrors with nothing to reflect. The hum stops.

He listens.

Silence.

For a long while, silence.

deKlend listens.

Then she bursts in on him, her silhouette in the dark room, spins into a blur, transparent grey spindle, a sinuous waterspout, permeating the whole room with a low sound of her breathing. The breath of a girl is always pure. She spins slowly. Ballet practice. A forbidden body my body made. Her hair the flying anemone, sinking, now so fast pressure—I did not invent my body—too close, the crushing pressure flying out from her spins.

*

A vast ruined face, just on the horizon like the sun. He is cutting across a camp of construction workers that ascends wooden scaffolding and continues on the roof adjacent to the site. There are tents in little dishes of snow, little more than rags and tarps propped up on pieces of lumber—a cooker—trash—empty, except for a man with a scarf over his head, rocking.

There is smoke from the moon, a long plume of frail white smoke. Its light falls on brilliant red yellow and purple buildings, unlit streets swarming with tiny lanterns and candles carried by the people thronging them. The moon’s light falls on white roses that grow from white ceramic tubs, pigeon girls darting past whip by in a whirring cloud of echoes and afterimages, a sharp smell of their sweat.

Let’s try that direction (he thinks, not in so many words)—

The vacant room, with a few bits of trash littering the floor, is part of a suite of offices. It’s necessary to go through another room, with a sizeable metal desk in the middle, to get to it, and there are pieces of paper that are rain collected in the shallow hollows dimpling the top. For a moment he stops, deKlend does, a little too close to a doorway, brighter sunlight, still dimmed by dense overcast, thinking that he can just barely fail to hear a voice raised in what could be a warning; the sound throbs up and fades as though it were lifting itself with effort. Its tone conjures up a sketchy image in deKlend’s mind, of workers moving something heavy and too big to see around, so that another one has to guide them, and that other is calling out to them to stop, perhaps because that heavy thing is about to break loose and crush him. It seems he’s been turning that cry over and over in his mind, whether or not he heard it, for a long time, although it seems too short to speak of remembering it yet; it has ceased and it hasn’t yet.

Going through the doorway with no door—that’s it, presumably, leaning in the corner to his right. There’s a narrow window just about opposite him, the sill comes down nearly to his knees, and through it he sees a small paved open space like a quad not more than a couple of dozen feet across that forms the common area between the offices. One side is buried in climbing vines, like a tangled shadow. Satin sky overhead, the light is dim and even. A large figure emerges from the narrow arch in the wall and crosses the quad with long booming strides that shake the ground. It is all veiled, in a voluminous haystack of floating robes, black on black embroidery, and a hat atop its veiled head the brim shielding the fiercely staring eyes beneath. It moves with a kind of haughty exasperation and impatience, not seeing him, plunging in among the offices.

The figure does not turn its coldly burning eyes on him as it passes the window where, he feels sure, he is sufficiently conspicuous to be seen. In his dreams, he would sometimes catch a glimpse of a large figure all veiled, impressively dressed, although he’s encountered a man with a black wrap about his midsection, squatting there in the corner of the room he’d lived in eight years ago, a black wrap and nothing else on his enormous, powerful body, but it was veiled anyway in a shadow that was bound to the head, the upper arms and the thighs by twine. He’s encountered a stinking man

all in shreds, layered in long ragged veils one on top of another. And even then, as in every other case, the childish thought would come back to deKlend—what makes me different from this man?

Was it the same one every time? Every time, in a single dream? Was it the same dream? The same night? In any case, always the same question, and the same judgement, and one other, somewhere in there. Before he’d seen the figure he’d been discussing something in dream talk with some others, and one of them, all smeared, said to him he needed seasoning. Then he’d seen the figure again, right along the ridge above him, taking long impetuous strides, the veil catching and jerking free of the brush lining the path.

deKlend says to himself, glancing down, well, I can’t appear to him like this!

—Like what?

He might get the wrong idea (deKlend thinks) and mistake me for some shabby, capering little good little fellow.

There’s hollow breathing in the next room; deKlend listens, motionless in agonized suspense, cold sweat on his face, trickles down his back. He doesn’t dare breathe himself for fear of being heard by the breather in the next room. He gasps—

A rolling plain, covered in cream-colored stubble, and silver against the dark grey soil, same overhead, and one of the shadow trees turns out to be him, good old Veily, again. Although deKlend is sneaking up on him, deKlend moves quickly, thinking that the faster he moves, the faster whatever noise he might be making will stop. Having drawn up behind the figure almost too close without evidently attracting its notice, deKlend reaches down to pluck up the hem of its cape, several feet of which are trailing on the ground. There is a crease in the hem, but his fingers keep slipping off from it, and the cape does not move. Reaching down to lift it, he can barely get his fingers under it—it’s heavier than lead, impossible to budge. Looking up he meets the constellation glare of the figure, who has turned his head to him

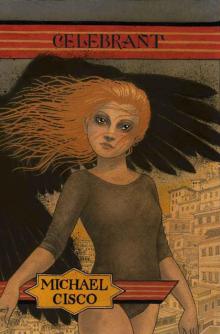

Celebrant

Celebrant