- Home

- Cisco, Michael

Celebrant Page 7

Celebrant Read online

Page 7

A huge grimacing steel mouth in the factory wall emits the celestials, blowing them like bubbles from a nozzle set between its teeth. Bubbles take human shape as they sink toward the ground, a dull matte transparency like a dusty vinyl balloon. They smell like halitosis and each has around its neck a folded white collar with a triangle of white beneath it, like the bit of shirt exposed above a high vest. Once formed, they join a streaming wind that circles the inner wall. The celestials don’t usually get involved in affairs not directly bearing on the factory. They do not police the city.

The insulation conjuring room in the City Factory is red and tinsel and very cold; bundled up, men in caps and women in kerchiefs, the workers dance in place, divided into ranks by enormous steel cables that they rub with special bows as they dance. These bowed strings are also fingered by a cyclopean hydraulic hand on a vast fretboard behind the workers. Snow falls from the air around them and big flakes of heavy ice keep splintering off the sides of the ghost containers and crashing, scattering broken fragments and ice dust on the floor. A metronome keeps the time, but it becomes inaudible the moment the hydraulic rams powering the hand start up. Supervisors situated above the main floor, in alcoves like spartan opera boxes, watch the dancers. When one becomes exhausted, the supervisor’s hand shoots out, pointing, and a runner zips in along a trench sunk below the level of the dance floor, pulls the collapsing dancer down into it and carries him or her off to the cots in the resting bay. Meanwhile, another dancer is dispatched, coming from the other direction, down the trench to replace the spent one. There are supervisors ensconced in loftier boxes to replace exhausted supervisors as well.

Watch as cobwebs of lambent blue gossamer draw stiff filmy lines inside the chamber. Then eyes sink, like pits, into a black cloud. A halo of shuddering light—the ghost climbs the ladder—some rise into the bulb above, in other cases the maxwell devil switches the tubes with a clank and the ghost is drawn into insulation like silk, forming the filaments into sheets.

deKlend:

The Madrasa is a backwater and the knowledge, if any, that it imparts is not portable. It stays in the school like animals in a zoo, and the students merely come to visit the knowledge. Some trek in on the mountain roads that run like narrow gutters between ridges of stone with softer infillades of puzzle rock, that only just lean back from the vertical. Every day a sleek, cyclops tram of enamelled steel like black glass, piped with chrome, with a bullseye lamp front and center, emerges from a tunnel to release a well-scrubbed handful of neatly dressed students. They carry shiny leather satchels. Others evidently live at the school, which continues not to make any provision whatever for them. They fill blankets with straw, roll themselves up and together like heaps of tamales, sleeping for days at a stretch in doorways or drooping from holes in the ceiling or stuffed up the chimney. The chemistry instructor goes to retrieve his jar of formaldehyde, a wave of stale air meets him as he opens the cabinet and there are two or three puffy, blinking faces in there, students rolled up in the shelves, tearing up the few remaining books and burying themselves in ripped-out pages.

This is in part attributable to the punishing cold; a searing damp cold that doesn’t seem to be affected by the actual temperature.

deKlend, with his perennial shawl and blankets, can feel the moral weight of envious glares from the students and faculty.

If it would get colder (he thinks irritably) then we’d all go numb and not feel it at all. It’s managed to get only just cold enough to make you nauseous.

The faculty are inured to it, and the cold doesn’t make them sick, only wretched.

The grounds include an extensive hedge maze of yew, or box, or both. At least it is called a maze. Actually it seems to be a series of barriers with switched-back openings, some of which are neat arches while other, shapeless apertures, are clearly the work of impatience or rage. And axes. The maze is made impassible by the students who have crammed their makeshift shelters into it, turning it into a smouldering warren of trash shacks. Students wrapped up like living sausages sit cross-legged on the ground beneath tarps or loose planks, miserably reading their textbooks and then tossing them aside into the flames of their thickly-smoking fires.

Who knows why they come here (Nardac muses to deKlend) We never offer them degrees.

The skeletal instructor is propped against the widow’s tomb, a heavy steel fire extinguisher dangling from one hand, distraught and worn out.

They’re always setting fires! (he wails, addressing no one in particular)

Evidently the students combat the intense, damp cold of the classrooms by lighting bonfires in them, sometimes in the trash cans, often simply on the floor. Nearly every room has scorch marks. Somehow the task of scotching these conflagrations has been delegated to this half-mummified old man, which might explain why an entire wing of the spacious school building is roofless and unusable, if not why it continues unrebuilt.

deKlend wanders from room to room in search of tinned food. He pauses for a moment, having met with no success, in what might be a common room for the faculty.

His attention is arrested by a thin, russet-colored book stuck in the fissure behind the broken pay telephone on the wall. deKlend plucks it out with a flick of his finger, when the music instructor suddenly staggers through the adjacent door. Surprised, deKlend puts the book back at once and then wonders why.

It’s not as if I’m snooping (he thinks)

It’s already beginning, as he realizes, to dawn on him that he’s entirely too self-conscious, but this kind of thinking has an implacable momentum of its own.

It’s more like I’m in a clandestine mood. The mood to be clandestine. This is very poorly expressed, very poorly. What it is (he thinks) is the idea that I don’t like to be seen to be transparent, no matter what I’m doing. Even, or I should say especially, when what I do is insignificant in itself. I should prefer always to be—

His way of thinking to himself is smoothing out, it seems to him, as the minor agitation of his surprise subsides,

—a cool opacity.

He looks on this triplet of words, visible in writing to his mind’s eye, with a soft little sensation of pride.

That is well put (he thinks)

The book slides down and drops straight to the floor, splat. The music director stops shuffling roughly midway between the door through which he entered and the door that is obviously his intended destination and turns to deKlend, lightly raising his heavy eyebrows at the book.

The precentor wrote that (he whistles through his dentures, pointing with his eyes)

Turning to resume his journey he adds, I wouldn’t waste my time with it. It stinks.

The book lists no name whatever for the author apart from ‘Adrian Slunj.’ The title, printed in red ink faded to brown, unless it were always brown, is Night Anthems of a Ghoul. All the printing is brown, and cold has warped and stiffened the pages.

This corner seems to want to dogear itself under my thumb; the previous owner (he thinks) might have left an old crease there, although none can be seen.

He reads from nearly the beginning—

Engulfed in their individual inflammations, screaming ghouls gnaw viscous goblins beneath a putrefying sky, ah, now! flayed and drunk, the surcingled vampire writhes, gnashes his fangs on his bed of caustic dust, and, above the walls at which he snarls, lances of witch ice bend to seek unerringly their own wooden hearts, spitting them with howls of demonic agony and bitter shock... chattering imps, their buttocks ablaze, imbecilically pursue a dotted trail of gold only to find at its end—a grave, waiting, each for each: a puddle of frigid detergent for each sizzling ass, and as their squeaks are cut short with a hiss, pigs with elaborately coiffed human heads wallow the grave marl over them like cake crumbling into downy heaps.

Gardens of contaminated porcelain tinkle feebly in the smarting wind, a thin smoke of fever grain flickers up invisibly from the trumpets and coracles of the flower... the shadows of discarded umbrellas are gathe

red up and pressed into a book by the phantoms of dinosaurs dead for eons, who swiftly melt into the felty gloom again when the horns of the virgin revenant groan like aged boughs in the forest’s still galleries—her leprous hounds plunge frenziedly into savage brackens and in moments are slashed to slimy, mustard-textured curds—clear, lethally radioactive thorns four feet long fold as complacently as priest’s hands to shield the numb coitus of the jellies.

Candy-colored leaf litter seethes with intelligent living mucus, brilliant and tormented; its glistening slaves are, unbeknownst to it, trapped in a silent gale of hot winds and waters, the evil dream of a balefully senile moon that sunders the reeking banks of stale clouds with its unintelligible demands. Ardently anticipated festivities are crushed beneath huge idols, churning up grisly pulp like stone rolling pins, smiling blandly with loose lips pearled with ointment. With a bray of despair, the lamia immolates herself in the festering pits of the charnel whores, where severed livers sob and strangle their victims by filthy torchlight. She will retreat to the valley of meditating blisters, where the empty scrotums of dismembered shape shifters throw old pots on cinnamon wheels. Tapestries squired from ducked flames wave over basins of acrid fuel—maddened with coarse language and banshee breath, brawny ghosts pound translucent silver wardrobes to splinters with tombstones in mammoth cranial mortars while the scooped-out brains, like a flock of slick, headless sheep, huddle indecisively in a still corner of the Adipocery.

Tripe (deKlend thinks)

He leaves the book on top of the telephone. The weather is starting to lour in through the windows, and he resumes his search for something to eat.

Later, looking out at seething night air, oceanic with undulating webs of sleet. Just as expected, out of the darkness lunges the head of a sea turtle, and its flukes below, slashing at nothing like the wings of a bird struggling to escape a man’s grip. The beak in a face like a knight’s helmet snaps at the icy particles that sway against it, and sight is darting from its gemlike black eyes. It dips in the air, turns away and then a little toward me again, and I see it has two long, sturdy if slender legs, in black wool trousers, sharply creased. They look like deKlend’s legs; his face appears next, gleaming with perspiration, hair hanging down over his brow, and, seeing him, that is, himself, struggling too close by, he calls for help. He has the turtle by either side of its buckler-shaped carapace and it is thrashing its hind flippers against his chest. Stepping forward, just then, as perhaps he has loosened his grasp a bit involuntarily, anticipating help, he cries out as the turtle shoots from his arms like a bar of wet soap and sails head first out of the pillar of light there in front of the dormitory. He lunges after the turtle, slipping and bending sharply forward at the waist to avoid a fall, while deKlend darts after it himself. Nothing there. As he’s about to turn, he happens to glance upwards in time to catch sight of a shadow of motion ascending among the firs further down the path. He peers attentively after it, but there is nothing to see now but dark, and the perennially resifted sleet, floating like long hair.

In Votu:

The chief rabbit girl is a brawny ten-year-old who’s big for her age. Her given name is Kundri. Naturally, the others had no sooner learned this than instantly started calling her Cunty behind her back—or from a safe distance. But when she got wind of it, she preferred it.

Yeah, I’m Kunty.

She smiles, showing all her formidable teeth.

Kunty maintains that she owes her unusual speed, belligerence and physical strength to the peculiar excellence of that-organ-for-which-she-is-named.

I got a good one (she says, rubbing it proudly through her skirt)

Kunty is weird even by their standards, and might have been a half-wit or insane with her way of snarling, her depraved, creaking voice, her infectious recklessness, her inconstancy and violence. A characteristic gesture, rubbing her bottom in little circles with the palm of her hand, fingers bent back.

No one crosses her. She is surprisingly strong for her size. Her body is dense, corded, and supple, with thick brown hair on her forearms and all up her legs. Her blackened fingernails and toenails are as hard and pointed as claws, and she sharpens them by raking them along the polishing ground with an unbearably harsh grating noise. The others squirm and clap their hands over their ears—Kunty observes them with a leer. She has the special hinged backbone found among rabbit girls, which enables her to run swiftly on all fours, and enormous incisors, each the shape of a coffin lid. Big as they are, they don’t protrude, her closed lips just cover them, making it all the more alarming when she talks, smiling, saliva bubbling around her teeth like hot oil in a skillet.

Kunty has a justified reputation for ferocity. Once, after she’d been caught stealing vegetables from a cart and the owner assailed her with a laundry plank, Kunty bit her in the throat and left her lying there on her back. The woman survived her injury, although the same cannot be said of her power of speech. A wide pink banner of satiny scar tissue under her chin stands as an advertisement for Kunty’s savagery.

Most of the time, rabbit girls are occupied in finding food. Water can be tricky as well; the heavy water used by the celestials is toxic and charged with bachelorization energy, and there is no river in Votu. Its water is drawn from springs, and circulates throughout the city in sealed ducts of basalt or marble. The girls have to make the rounds of rainwater cisterns.

The city’s food is grown in plots outside the walls. The vegetable rows are divided by lattices of clear glass; each field has a large bulbous timer, like an old-fashioned onion pocketwatch, buried in its center, and the farms buzz with their hollow ticking. Fertile fields hum like looms, the plots are surrounded by closely-spaced metal shells like fanlights wired to the timers and to batteries of neutral energy from the city factory. At intervals, they charge, flooding with trembling rags of wan current that growl against the metal like the razz of an arclight. Invisible elementals saturate the ground, cracking seeds open with eardrum hammers, tugging at and stretching the leaves, lengthening the shoots, inflating the vegetables like balloons, working to raise stalks of grain like drawbridges... Or these are the things one imagines, watching all the plants quietly shimmying, boogie-ing to and fro in the ground like dancers making the round of the dance floor. Various measures are taken to keep the rabbit girls and the big blue deer the Indians call nilgai from getting at this food and for the most part they work.

Joining rabbit girls involves stealing at least three oranges right off the trees. This is risky. The oranges are watched, but only when they’re ripe. So the girls steal unripened oranges, and even then there are watchmen to be avoided. These oranges are grown with the fertilizing assistance of the manurancers, manufactured at the city factory; the manurancing energy dissipates when they are fully ripe, but the underripe fruit will not yet have converted all its charge. This, transferred to the eater, causes the ears and nails to lengthen, the incisors to become more prominent, the back to become hinged, the corners of the eyes to alter their pitch, opening diagonally on an extended field of peripheral vision. Hence, rabbit girls.

They live by theft. If there’s trouble, rabbit girls disappear through basement windows and into culverts. The celestials don’t police the city, but once in a while they are directed by their minders to pursue rabbit girls who steal things in the vicinity of the factory. Once, when a minder officiously told her to step back from the factory wall, Kunty threw a lump of donkeyshit at him and had to flee from a celestial. In short bursts of wild effort she can reach twenty-seven kilometers an hour, becoming briefly the fastest-moving thing in the city. Kunty knows from this experience that the celestials have a limited ability to pass through solid objects, so anyone who thinks they can elude them by adopting a zig-zag path, and thus interposing obstacles to pursuit, is only hastening his capture. It’s the flight in a straight line that confounds them. And they can’t run on all fours like rabbit girls can, so with the speed of their arms and legs combined, rabbit girls can outrun the celest

ials.

These are the girls who survive exposure and come in from outer space, as the area around the metronome is called. They trickle into holy-shaman-city-Votu because salvation, of a sort, is possible here. Some float in attached to balloons, others bubble up in the springs, or wander in off the steppe. Thanks to Whrounim taxes, there is a shortage of boys and consequently no gangs of boys to worry about. People who live in Votu have enough to go around, and murder and rape are rare occurrences. While it is interpreted in a variety of ways, the presence of the girls appears always in the light of some kind of blessing, as if they were mascots, totem spirits, good luck. Severest penalties are incurred by doing the least injury to any of them, or so it is said. They fulfill the role of necessary recipients of alms, and are typically left to their own devices.

Some manage to find homes. Some become rabbit girls. Others... These are unshockable—gone in an instant, in a flurry of motion. They have displaced Votu’s actual pigeons, as rabbit girls have displaced all the rabbits. Squirrels still can be seen elbowing along the whistling pipes and cables; there are no squirrel girls or not yet, or not any more.

...Pigeon girls, whose white droppings streak the sides of the buildings and eat into the concrete. They dress in grey rags and shawls and “tardoleos,” which is what they call leotards. Their blank, staring, dark-eyed faces, many of them the eyes almost completely dark, seemingly oblivious to cold, to anything but hunger.

They sleep in shifts, huddled on their bottoms with their heads behind their knees, like crenellations along the roof tops, while others keep watch impassively. In the streets they mill in circles, murmuring to themselves, scratching at the ground, and it’s impossible to tell one from another. At any abrupt movement toward them they burst out rustling, and vanish.

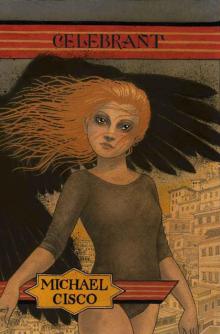

Celebrant

Celebrant