- Home

- Cisco, Michael

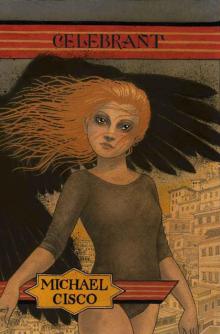

Celebrant Page 6

Celebrant Read online

Page 6

The grafticulture of the whrounims is unbelievably developed. The trees fold into each other, the forest canopy is all multicolored roses instead of leaves, and the gloom beneath them, velvety with petals, is so overpoweringly fragrant the smell burns in the eyes and nose with a sugary heat. They stroll the corpse way, where the path is lined with false charnel pits filled with plants that naturally take the shape of dead bodies, and that burst into huge stink blossoms, sickly pink leather punchbowls, that attract pollinating flies by counterfeiting the carrion reek of rotting meat.

The brilliantly-decorated domes and spires that overtower the campus are more numerous all the time; they come in all colors excluding only white, color of mania, and black, color of true love. The use of black and white is restricted in the subterranean dominions of the whrounims.

Although they maintain the Madrasa, the whrounims neither teach nor study, nor even appear there, and speculation about these unknown benefactors, their motives and even their physical nature, is rife.

Evidently, whrounim marriages are solemnized by cross-transplanting scalps. The whrounims are surgical wizards who regard every newborn child as raw material. To retain the anatomy one had at birth is considered barbaric, and every adult whrounim is an anatomical collage of micrografts from dozens of others.

They exchange tissue only from among themselves (Nardac tells deKlend), to avoid rejection.

Do they die? (he asks) Or do they simply keep freshening themselves up with new material, indefinitely?

I’m not too sure... (she says) But what’s the difference? How can they tell who they are, finally?

But there are many things you are not allowed to do, (she adds cryptically after a moment) The whrounims have all sorts of rules for us.

I don’t see any whrounims here (deKlend says)

I wouldn’t know if there were or not. I’ve never seen one.

Didn’t one summon you to the school personally? One did me.

Nardac glances at him.

Was it a tall, silent fellow? With an off-puttingly self-satisfied expression?

Yes, that’s him.

He’s no whrounim (Nardac says complacently) That was—

She breaks off, turning aside to sneeze violently. Once. Twice. Three times.

Here it comes aga—

Four times. Five times.

Oh!

deKlend gazes around himself. Peal of smile... the bell... the knell smile... the unspooling ribbon of haloes of holes, a ribbon from above admit sunlight into the dark tower... a complicated asterisk of smoke from the bowl... the sun appears at the groin of each arch as he passes. The toll of the bell breaks out here, then vanishes, to reappear way over there, rising in a fading crescent of sound, passing secretly through space so its continuation is like an answering bell responding from the distance.

Nardac rubs her nose with her talons.

He’s the precentor. Adrian.

She sniffs, fighting off another sneeze.

He rings the triangle every day at the beginning of session.

From a group of students nearby comes an answering sniff, like a sound of ripping paper. The whisky-like smell of the canal flips once over him and drifts away with the echoes.

He didn’t open his mouth, did he? (she asks, suddenly uncertain)

No. I remarked on that.

That was him. Adrian never opens his mouth if he can help it.

She screws her features up a little in distaste.

Worst case of tongue thrush you’ve ever seen.

The path narrows, and deKlend has to draw in too close to Nardac.

Why do they bother with the school? (deKlend asks) What’s the point, if they don’t attend it themselves?

He wrote a book you know—what’s that? Oh, there are as many opinions about that (Nardac says) as there are people here. Personally, I think it’s a sort of whim.

deKlend takes in the facts without following them too closely.

No one seems to know what whrounims look like. It’s not that they possess no racial characteristics—just the contrary, in fact. The whrounims give the lie to the notion that different racial characteristics arose among human populations as they divided and took up habitation in the world’s different climates and terrains. Among the whrounims, babies are born exhibiting the entire range of human characteristics, of all possible so-called races. They maintain that this is in keeping with the archaic, original nature of mankind; that even within small, isolated communities, the earliest human populations were, they say, astonishingly diverse, so that each generation expressed a wild sampling of phenotypy. Because of this great diversity, early human children only rarely resembled their parents. Children normally looked nothing like either parent.

However, as humanity grew more numerous and dispersed, and as certain human societies began to place emphasis—with mounting insistence—on demonstrable familial continuity (in particular where the transmission of hereditary privileges and property were concerned), and in the dividing up of family groups and so on, parents began to reject and abandon—and even to kill—children who did not resemble them, sparing only those children who did. It was this that brought about the current state of affairs, in which children all tend to resemble their parents closely. Unaware of their history, people invented stories that stood the truth on its head, insisting that all humanity began with basically identical individuals and only became differentiated later. Being the same was made to seem the more natural thing, when that sameness was actually the consequence of deliberate and willful intervention.

The whrounims had not gone that route. They continue as various as ever, and traits and qualities long vanished in all other human populations (with the occasional atavistic exception) are said to persist among them, and to be distributed surgically.

So what does a whrounim look like? (deKlend asks)

Everybody, I suppose, (Nardac answers)

By now they’re passing along a gravel drive. As they watch the brown sky thickening with the onset of artificial night, brought on as the whrounims dim their distant city lights, a convoy of silent trucks with shimmying metal tanks on their beds goes lumbering by. A sound of crying babies is plainly audible, coming from the tanks.

Those are full of babies, (Nardac explains pensively)

What on earth for? (deKlend asks, his large eyes widening in astonishment)

Whrounims don’t tax in money, but in male offspring. The firstborn from each couple.

—They don’t eat them (she adds after a moment, grinning sadly) I think they make them into soldiers, something like that.

The real problem is the girls. Since the parents have to give up at least one male child, and since they value boys more than girls, they get rid of baby girls. They don’t keep them. I think they regard girls as a luxury, or a waste of time and of food. They keep trying to have boys and, when they get girls instead, they get rid of them. They leave them out for the birds, or throw them into deep gullies, or pools. Some they tie to kites or balloons and let loose on the wind. And no one, anywhere, talks about it. A girl’s birth they call a ‘false pregnancy.’

The subject seems to depress her, and she wanders off in silence, without saying goodbye.

deKlend returns alone. The halls of the school are deserted. No quarters have been found for him yet and he will have to sleep a second night on that narrow sofa in the lounge. A dish of bread and fruit has been set out for him, though.

Lying in the dark, he listens deep into the silent fabric of the school. In one of its secret rooms a receiver is tuned to the wandering signal of Black Radio of Votu. Its squelched, whirring voice says:

apencindybdiasndukmdnbdujdnysioedbeuenbdhjdbhdnbhdwiwygdhuwndyithndywodfjndgborthshamnenoquenotheuwmndyiwnduyjwjthdiwhdfhgncousbjneoundidmfiepcvncyeifpvjhcndoieyfmdoitrolgviotughdbwyvnjfuiencxuwjdusnsuemxciovncgsmncnckjgsnmjhudmsdjusdnewdcsmnemosemturnfherdufdplvfnmviuremvuhdofnfirnmfdydnetwvxowmvpoxcldlemxpslekohfieponbofboerjidmurnpeindlbmxodkfopendkdoioecihlbbso

osismonamtiatosfsh

Listening to that sourceless voice, travelling through the walls from somewhere, he experiences the floating anticipation he gets from listening to songs, when a verse ends and the next one begins while the music doesn’t change. It’s like a soft blow, or something yielding inside. The murmur goes on, a steady tone with a warbling distortion running through it, like another voice hollowly encompassing it. The music director, looking off into space, shakes his head. Static gushes from the speaker.

deKlend tries to sleep.

Sleep, by which I mean a discontinuous series of solitary gymnastics in sweat-soaked blankets in an airless room (he thinks bitterly)

While they ‘sleep’ in canals lined with clove trees under hooning woodwinds.

Abruptly he lifts his head and looks around. The music director is no longer sagging behind the door. deKlend is alone in the gaunt room.

Again he is pierced with an unaccountable pang of intense fear. He tucks his clammy hands under his arms to warm them. Cold nausea settles ponderously down on him. He lies flat on his back, his head propped up on the armrest, uncomfortable, and convinced he’ll vomit if he moves. The stink of institutional food in his nostrils sickens him, he begins to hear orderlies walk the hard waxed hallways outside and the abrupt, resounding noises of a hospital ward. His breath erupts from his mouth, and through his own irregular gasps he can hear the muttering of the orderlies...

The idea has its moment. Miss that moment and, even if it can be remembered and set down later, even if it is set down word for word as it was, the delay will have killed it.

Reason is the magic. Remember that at all costs, even if it must be cut with a knife into the body.

A child can see it—the magic—but the child won’t be able to understand it. The attention of the mature person is fixed on plans which won’t come to fruition for a long time, if ever, and from which they divert themselves with hasty half-snatched one-quarter-pleasures, and this costs them the sensitivity.

That’s it (deKlend thinks, quaking with terror under his thin blanket) Think slowly and methodically, don’t skip ahead, not a single step. Articulate each thought distinctly to yourself, elaborately—drag them out, grind them.

The skilled practitioner must cultivate a sophisticated reason. This is why magic is uncommon. Those who have the vision usually lack the reason, and those with the reason usually lack the vision. Only the one with both reason and vision will be able. What has been underway—

His teeth grit in a spasm of fear, and he sucks breath through his teeth.

—prayerwalking is walking in place/in spirit, walking homeless in the spirit. What is the spirit?

His eyes stare up as though an orderly were bending over him now, clutching some steel implement—

THIS is the ‘lurking evil’ (he thinks) The evil force threatens me with the sanatorium—

He takes a deep breath and holds it, his skin icy and criss-crossed as his every hair stands on end.

—The enemy!

He swallows arduously. It’s like engulfing an egg.

...Reasoning: This theme will have two aspects.

deKlend concentrates doggedly, desperately, on the pedagogical tone, a classroom, a boring seminar, the most boring, the most pedantic teacher imaginable is rattling on to him about the theme having two aspects, one, the more obvious, being the possibility that deKlend is an inmate of an insane asylum and all of this stuff about Votu and the Madrasa and the Bird of Ill Omen is his hallucination, through which the sanatorium can be glimpsed when the delusion wears thin and now the full storm of his terror shakes him like a rag... the pedant quails against the blackboard, a huge shadow gathering its darkness before him, but somehow, through chattering teeth, he continues the lesson:

S-second is the p-possibility that the sanatorium itself is a menacing s-spirit—

His face twists wildly.

—like—

—A MONSTER!

(his voice rises to a shriek)

—A DEMON!

This outburst unleashes his words and they erupt from his mouth in a complicated rush, like verse, hastily-recited, but distinct:

A demon that closes around you when something about you, a thing that involves your personality, your power, your imagination, your freedom, which in toto I shall henceforth refer to as your principium individuationis, is damaged or grows weak or is over—

He swallows quickly. He must finish before that slinking shadow reaches him.

...It is reaching for him now!—

—overpowered—when your principium individuationis is damaged weak or overpowered the sanatorium begins to materialize around you, like a pneumacidal web. You begin to see the corridors, the orderlies, smell the food, the body odor and the disinfectant...

Is it receding?

He listens, straining. He searches the dark for any sign.

No, there is no click of heels. There is no bad smell.

There is the must and gloom of the faculty lounge. The dim brown light outside the narrow windows.

deKlend lies back and draws up his blanket again.

It’s not finished (he thinks)

Neither am I. I learn from my mistakes. When I take notice of them. I often do.

Still listening, rallying, relaxing, his confidence returning again.

With my own hand I’ll write myself, now. I won’t get trapped like that any more (he thinks)

In Votu:

Trees skirt the city wall, and dash against it in a continuous tune wind, like surf. The upper portion of the wall is skirted by inlaid mosaics of sensitive architecture made of nerve material, maintained and sampled with hyponic needles—they repeat the echoes. There is also a continuous inner wall that surrounds the city factory, where a certain variety of energy is produced by dancing on rugs. These special carpets are produced only in Votu, and virtually none have ever been removed from the city. It’s said that a curse of some kind will fall on any who take a carpet out of earshot of the walls.

The weaving of carpets of any kind, dance carpets included, is work reserved exclusively for Votu’s women. Dance carpets are made in keeping with the Votuvan idea of time, using only forgotten patterns, which are spontaneously recreated, not at random, not intuitively, by the weavers as they listen to old music. They gather in time-honored workshops, not in the factory. One wall (at least) is open, the looms stand in a circle, the musicians play outside. The women are all former dancers, who frequently heave themselves up from their seats and go to dance in the clear spot at the center of the shop, in a deep and serious groove. Their dancing is strenuous and dignified but not extravagant, not demonstrative, not solemn; they listen down into themselves and then wheel out like boulders suddenly turned into tops. Lifting their thick hands and heavy arms they motion with stunning elegance; the severe looks of this one, the sweat sparkling on her cheeks, now melt calmly into a benign expression of motherly delight. They’re telling stories to each other in gestures dense with unmistakeably articulated meanings. The dances of patterns involving patterns are recorded in the carpets and can be danced back by other dancers who know how to retrieve time.

The dance rugs are alive; they live and heal. They don’t need to be beaten out, because they eat dust.

The carpet weavers traditionally marry the craftsmen who produce Votu’s one and only export. Oblate globes of glittering steel in concentric fine circles or spirals, streaked with lines suggesting the globes might be made by braiding. There seem to be two hemispheres that fold out into solid rims at the join; from each hemisphere protrudes a bullet-shaped bulb with a smoothly receding hole at its tip and, two small sharp holes at the base. The bulbs protrude at an angle parallel to the planar section of the spheres at their widest point, and are positioned at forty-five degree angles to each other, although this is sometimes to the “right” and sometimes to the “left.” These balls are produced in total secrecy and no one at all knows what they are for, including the traders who come to Votu to b

uy them. Likely the craftsmen don’t know either, but they are sworn to complete secrecy in any case. They are made solely for export; they wander away, changing hands from trader to trader in city after city, because no one else in the world can make them, and because there are people who reside very far away—so far away, they might not even be human—who pay an excellent price for the globes in any quantity and at all times.

Even though these essential goods, carpets, awnings, and the nameless globes, are not made there, the city factory drives the metabolism of Votu, and it must therefore be defended. The first police had been automatons called ecstatics, who proved impossible to control. Everyone was terrified of them, because they killed. Those who were killed by them vanished without a trace, from the city, from history, from memory, as if they had never existed at all. Fortunately, for reasons of their own they all deserted the city, never to return. There is nothing further to be learned about them. If it weren’t for the persistence of the records, one would think they had killed themselves.

Their replacements are indignation-elementals known as celestials. These are tractable, all but invisible anthroforms, with no minds to speak of—a minder is required to set them on someone. Since they consist only of tenuous matter, tough but exceedingly light, they have great speed and strength; they apprehend their quarry by jumping their outlines around him and then walking him to the lockup, like a living suit of clothes. Such prisoners are conspicuous, walking stiffly and deliberately, arms rigid at their sides, clothes flattened to their bodies as if they were soaked, rolling their heads, shouting pleas and curses. When the prisoner is in his cell and the arrest is complete, the celestial dies—apparently of sheer delight—melting into a dry fluid collected by a sluice in the cell floor to be pumped back and recycled in the Indignifier.

Celebrant

Celebrant