- Home

- Cisco, Michael

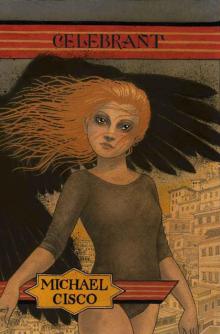

Celebrant Page 9

Celebrant Read online

Page 9

deKlend runs after it, reaching, clutching handfuls of air. His face is drawn with fear, despair, hope and agony.

*

Nardac and her special friend are sitting together in a shrubby hollow beneath the stone wall. It’s an unusually bright day for these parts, and they thought it would be fun to put on their sun hats and loose Isadora Duncan frocks, and have a picnic. They tiffin on divinities, egg salad sandwiches and cold beer.

A regular thumping sound and a curt ejaculation of what sounds like intense fright alerts them—suddenly a huge dark thing hurtles over the wall, right over their heads, and drops instantly out of sight on the far side of the hollow.

Whatever it is thumps away; its shrieks echo in the midday stillness.

The two ladies are frozen in attitudes of surprise. When Nardac looks at her friend, the other is gazing back at her, round eyed.

What an enormous bird! (her friend says breathlessly)

That’s no bird, (Nardac says at once) He’s a guest here. Or was.

*

Stumbling, he flings his hand out and, before his eyes, he sees his fingers close convulsively on the bright filament.

He stops short, his closed fist dropping toward his abdomen, and looks about him, as if someone were calling him. Breathing hard, he glances this way and that, and then, startled, he stops. He has in confusion a flashing impression of the wheeling of the stars, majestic and remote, as if he’d come loose in space the moment he grasped the filament—then a nightmare stirs itself, rising like a god from the trees and the crumbling stone wall and the edge of the school, shouting from the mountainsides and steaming from the grass.

Something invisible is streaking toward him out of the blackened trees. Without warning the ground tilts beneath his feet, precipitating him forward half falling half running. He dives over the ground his face white with terror, not fleeing but he must not fall—must not fall—up comes the stone wall and he bounds over it and lands with a jar that buckles his knees and nearly sends him sprawling—with a yipe of sheer fright he wrenches his left foot forward in time and continues—what? what?

You wanted out of here, old boy.

With every breath he shouts, hoarse and ragged his voice, roaring in horror.

Let go the bright filament and stay here if you like. Otherwise, you’re going over.

From far away shadows that instantly lengthen reach toward him. The land all around is impassive, scintillates in the bounds of each painful, shattering step, to break up and spin in tangles. Now great slabs of color in the void erupt ahead and sickened he pitches forward and his outflung foot swings down and down until it passes the other and comes up again behind with nothing to meet it as he goes over.

Corridors of the sky

In Votu:

Dance is the most important art. All the power for the city factory is produced by legions of dancers, and there are many other varieties of dance. There is an extensive repertory of dances to be performed in silence, or in darkness, or both, and there is an unrecognized naturalist school, associated, it must be said, with certain reactionary elements in society despite its claims to be avant garde, which hides itself as the “dance of everyday life.” Sexual dance is at once highly ceremonial and spontaneous; interference in such dancing is a high crime punishable by summary banishment. It seems sexual dance is preferred to undanced sex, even though it, by its nature, is not something that can be realistically done every day. It’s quite strenuous.

The practice of sexual dance originates in the particular observances associated with the natural robot nicknamed “spider,” or “sea star,” or (most commonly) urchin. A dark body bristling with tubular spines, and resting on a single hydraulic leg, urchin usually haunts the curtained alcove in its shrine, surrounded by chambers and alcoves, many of them honeycombed directly into the thick walls. A thick scent of sex trickles from them. People go to the shrine to perform sexual dances in the presence of the robot, which seems to radiate aphrodisiac forces. The alcoves and little rooms are swathed in thick curtains and rugs that are changed by the mathetes after each use, and completely dark, because the anonymity of the celebrants, even from each other, is part of the rite. Couples who go to the shrine expecting to be together emerge again in confusion, unable to say whether or not they have remained faithful to each other, and no one is accepted who arrives alone at the shrine. Men are enjoined to be silent, but not the women, because it is believed, owing to the detection of certain peculiarities of its behavior at pivotal moments, that urchin considers women’s exclamations of pleasure to be music—perhaps even its favorite music.

All the natural robots respond immediately to music and dance; even when they give no outward indication, it is nevertheless obvious that they listen. Music and dancing never fail to stir them with an impulse to participate; they produce sounds then unlike any others they make, and move enigmatically, in their own way.

*

Black rags or straps or ribbons flutter from the bridge and out of them appears the falcon.

The grass becomes a uniform, shimmering diamond pattern. The shimmer bristles its hackles, undulates like water, lozenge-shaped areas of blur appear on it—it’s alive, whatever it is, not a shimmer or a blur or a pattern, but something in all these things. The dim figure there, walking along the edge of the meadow like a velvety blob of ink, is a yellow and black tropical fish from a magazine.

Look up at the crescent moon and Venus in a blue sky. Feel engulfed in the deepening blue. Hear the sudden gust of loud voices and be alarmed, but only for a moment. Those aren’t coming for her.

The grass darkens. The shimmering and dancing she sees appear is nature—striations, braided coils, the gleams of supple mail, and abstraction. Pigeon girls with dusty hair scatter and gather again in the streets. Burn walks with her hands behind her back.

A mathete wearing a black kameez is watching them, from the shade of an awning. His hood is thrown back, and the kameez is open at the neck, exposing a white satin shirt with a long collar and a drooping black bow tie. This marks him as one of urchin’s mathetes. He’s a rounded man, with a smooth face, circular glasses, and thick hair, perfectly white except for a single, thin lock, as black as ink, that sprouts from one half of his widow’s peak. It makes him look surprised, an exclamation point just above his face.

He waves his hand, scooping. Burn notices. Goes over to him.

Little girl (he says, in a vibrant baritone) Can you help us? We need to find a discreet spot, of a certain size, where we can bring urchin and urn together.

His face is bone white, and his gums are shockingly red.

I assure you (he adds) that this is strictly for sexual purposes.

Burn sticks out her hand.

The mathete shows her a coin. His hand like one of those white trombone-shaped flowers; a long, pale, and somehow excessive hand.

Burn purses her lips and then shrugs.

Poof—she vanishes. Darting up walls and over roofs she goes, searching, leaving a solitary footprint in the soil of a red clay windowbox four storeys off the street.

Fifteen minutes later, the black-locked mathete feels a poke in the back and turns. Burn crooks her finger at him and points the way, leading him so that he has to jog after her. In no time she is showing him the spacious shell of a building, a huge bare floor like a stage, brick walls.

The mathete looks around, smiling with approval or amusement. He swishes over to her and drops the coin into the palm of the hand she has patiently held out to him. She has only the pair of disintegrating, blackened ballet slippers on her feet and the grimy, colorless “tardoleo” that covers her from knees to elbows. In that moment each seems to forget the other entirely. Burn scampers off, and the mathete begins his preparations.

Burn does not go right back to the other girls. She gets up onto the roof, which is all big slate slabs. Some of these have fallen in, but the wood webbing they rest on is sound. Burn takes up a place with her back to the edge, where she can l

ook down into the room below. The mathetes pass through in a line, murmuring and dripping incense smoke that smells like toasted insulation. They chant in a circle. She doesn’t see the mathete with the black forelock singing. Another is chewing out long strings of elastic syllables. The chant ends with a long

—sssshhhh!

The mathetes withdraw to somewhere Burn can’t see them; but she can hear a shuffle of feet or a throat-clear now and then.

Then a shrill whistling becomes audible, coming around some nearby obstacle. Urn totters in beneath the roof on its treads, listing slightly over the minor irregularities in the ground like a novice roller skater, using its ‘arms’ to pull itself along. The floor groans under its weight. Whistling swirls around it like an invisible swarm. Now urchin appears, coming from the other direction with abrupt, jabbing steps that set all its spines jostling. The two hulks advance clumsily toward each other like blind giants groping toward each other in the dark. The building shudders. Urn whistles impetuously, the note changing up and down. Urchin, with a steady, nasal growl, lurches this way and that, advancing in short sweeps.

Urchin’s spines knock against urn’s sides and both machines lunge together with a crash and grind fiercely against each other. Urn extends its turbine drills and urchin shoves its bulk forward in short hops jerkily nuzzling at urn’s front, engulfing urn in a thicket of rattling spines. Urn rakes urchin up and down with the drills, then lances it with a six-foot bit—smoke races up the screw and the turbine ejects it at the far end in a whipping spiral. As its carapace is torn open, urchin rams a stubby auger into the base of urn’s goblet in a gush of sparks and a howling rasp that rattles Burn’s teeth. Screeching like a jet engine, urn drills into urchin’s body—urchin is pressed down then springs up again as the drill pops through its shell, its carapace gradually comes open, a ragged scalp of spines sags to one side exposing an engine-like structure that burps and shivers convulsively to life, wobbling so violently on its block that it blurs, splutters, gabbles, stammers.

Urchin’s auger peels back a star-shaped opening in urn’s outer wall, and thrusts a pair of circular saws into it, burrowing passionately into the aperture—urchin raises itself into the air with a hooting wheeze. Urn’s ululating drills ply themselves up and down urchin’s body sighing, shearing off sparks and smoke. Laboriously, irregularly, urchin raises its bulk, its roaring saws pulling it into urn, while urchin’s own electrified relays whinny and flash. The two machines are locked together and struggling like a pair of bucks with their antlers jammed together. The whole building reels. Urn reaches around urchin catching the whole body in a pincer, boring in from either end, and urchin is bolting itself to urn with hooked ratchets. Sparks, oil, hydraulic fluid and molasses spatter the floor, and small autonomous machines scoot and hop and slither away. The two machines jump and hiccup; with each spasm urchin’s spines bong together like chimes.

The two robots gradually stop moving, and the noise dies down to a meditative hum. Urn’s drills droop back on their arms nearly to the floor, and now sparks gush from urn’s mouth in a spray that nearly singes Burn. Urn’s form rattles with a rhythmical, grating clatter that repeats several times, gears gnashing and light metal blocks cracking like gavels. One of the drills spins sluggishly with a gentle crooning sound. Urchin emits a loud low hum that makes the window glass drop from the frames, the walls slouch, static bristles along the upper surface of the linked robots, its crinkling punctuated with a few bangs like wet firecrackers.

Then the noise begins again, as the machines disassemble from each other. Urchin lowers itself, trailing wires and small machineries, some of which tumble entirely free. They’ve exchanged parts and both are altered for the thousandth time. Pulling apart with snaps and churnings, loud thumps. A desultory burst of static dribbles from urchin. They separate. Urchin has several openings along its sides, over which its spines hang like stray locks, and it wobbles as it retreats. Urn’s goblet base now extends up one side along its entire length.

The robots are going back the way they came. Burn watches them go, rubbing her groin with the fist with the coin absently.

Phryne:

A man about thirty with tawny-brown hair and trimmed beard, well-dressed in a tight-fitting twill suit, comes down the gangplank carrying a valise. He wears no hat and his tie is so snug the knot angles a little out at the end.

She picks him out and begins to follow him as he passes the column. She appears to be an eccentric, portly man, with an indescribably weird fur hat and a superior manner. Now she bustles after her quarry. Her man is tall, and he walks swiftly.

She loses him at his hotel, but that’s all right. She needs a rest, and her mind is beginning to slip—she can feel it coming loose inside its outlines, and a quiet time in a dark spot will be required. He will be back.

Finally, that evening, he returns and, as he waits for his messages at the front desk, she is peering intently at him from a balcony, from within the image of a middle-aged woman dressed for an awards ceremony. Anxiously she follows his waverings—he goes into the bar. It’s time. She has rehearsed her part carefully. She changes in the ladies’ room.

The man stands at the nearly empty bar, taking in the hollow-sounding music and drinking his snaps without much pleasure. The woman approaches, very briefly preceded by her fragrance, and stands near him. Her voice, as she orders, is warm, soft, and low. She gives every impression of having just extricated herself from a bitterly disappointing date.

The man breaks the ice and they move to a booth. She finishes her drink while he’s only halfway through his second and he fetches her another from the bar and once he’s started getting the bartender’s attention she’s already got it into his drink. Fizz.

By the end of thirty minutes he’s conversing with her animatedly, his eyes a little glassy, his forehead starting to glow without actually perspiring. He takes hold of her hand and retains it with just a moment’s cling when she judiciously takes it away, looking at him in an appetizingly sad way. They part company with a lingering glance and an arrangement for tomorrow.

The woman whose appearance she’d adopted in the bar had discovered her man in flagrante with another woman—Phryne, again in disguise, and knowing in advance that the theatre was closed that day after all. Now she is free and angry. Disguised as the delivery man, Phryne sees to it the theatre is showing films about the revenge of wronged women. She restages a scene in a florist’s shop that had the woman smiling, in the visiting man’s form. Meeting for drinks later, Phryne, still inside his appearance, is nearly foiled by the sudden appearance of the original, striding by with a quick glance at his watch. Phryne’s heart plunges, wondering if he has another. She kneels meanwhile, feigning to tie a shoelace with her head well down and turned away from the street.

Fizz, they meet in the bar and in twenty minutes the woman is laughing woozily. Her date will escort her home and leave her gallantly at the door, a gesture she will remember when her head clears.

After a few more encounters, Phryne decides they’re hot enough and, each through the other, invites them to the house.

The woman arrives first. Phryne greets her as the man and apologizes for the lights—power’s out, candles are nicer anyway. The cordial is an aphrodisiac and she is warming the woman up before it’s half drunk.

Go upstairs, get ready (the man says)

The woman greets him at the door and is all over him at once. He doesn’t need any but he gets a booster drink anyway.

Give me a couple of minutes—then come upstairs!

Phryne is breathing fiercely through the nose. This is the culmination of a great deal of tedious planning, sifting records... but it’s also about luck, the chance. She must not miss.

They find each other without any trouble, and, in the dark of that room, with Phryne clinging to the other side of the wall, brother and sister embrace in ignorance. Phryne, her face thrust into a small, shadowed aperture directly above the headboard of the fourposter, is breathing

deeply. The draperies of the bed, the pads and linens, and the long gauze tapes that hang strung from wires all around her in this specially-prepared room next door, absorb the lovers’ compounds, and Phryne is basking in the air that the vents draw in.

Her mind clears, her wobbly self-possession grows more firm. Relief floods in and she is able to slacken her grip on herself without fear of disintegration. She rubs the air into her skin as though she were bathing in it. The tapes, the bed curtains, and especially the linen, are suffused with these essences.

Phryne is a lead addict, and naturally she is afflicted with plombosis, with its sudden, unpredictable abdominal pains and, far worse, its degenerative insanity. The prospect of mental instability, unreliability, terrified her, but she couldn’t wean herself from her habitual consumption of lead. Then she ran across those pages of the Fornicati Daemonorum which explain how the residues of incestuous intercourse, absorbed through the skin and lungs, neutralize the deleterious effects of lead on the mind. An opportunity to test this treatment presented itself, the results of this test were astoundingly satisfactory, and Phryne became an incest vampire from that day.

They’re not holding back (she smiles)—This should be very strong.

Every moment, as the panting, amorous struggle on the other side of the wall grows more exasperated, Phryne is at once rejoicing, more deeply winding in pleasure—and yet cooler, firmer, more bright and polished like a weapon, steady, her steely eyes glittering in the dark.

deKlend:

deKlend streaks headlong across open continents like a dive past the earth in a dream with no fatigue and without stopping he runs, wheeling legs, his loose hands turn off landscapes like blankets.

Celebrant

Celebrant