- Home

- Cisco, Michael

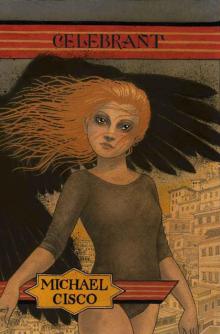

Celebrant Page 4

Celebrant Read online

Page 4

That arm shoots out and takes him in an unbearably strong grip, the figure is laughing silently at him and dragging him along again across a rumbling black and silver plain strewn with boulders that jump, totter, clash, and fall while the cape spreads oceanic night in their wake, like a high black canopy, melting and fine as mist, which sheds flashing dust, in long threads like rain tracks in the air. That tinsel dust is as fresh as rain. The stars shine through the transparent canopy. The drumming has gone below the horizon, and him with it. Now nobody stands there in the brilliant, clear fog.

*

Now what about that homelessness?

End of the world weather—clouds race along the sky, wind blows along the ground stripping the foliage from the trees for what always seems like the final time, blowing clean and pale and dead and cold and bright. The-end-of-the-world is always there in every moment, too close, right now, step out to the end, and back? Can you get back from the end of the book to now unmarked? Identify the traits of one who has stepped out many times: that person is all aswirl with intimate hypnotic spirals. Does anyone ever see a dream end?

The limpid air shivers with a resounding voice, booming from peak to peak, tolling across the plain to the rocky place where he hides himself. It does look like the vicinity of Votu, from the photographs. The ground is black streaked with white ribbons of clay, and chalky pebbles litter the stony floor of the steppe. There are boulders, too, and these give him pause because he remembers vaguely something minatory that is supposed to happen in the vicinity of such boulders. The voice is booming all around him now, calling something like “boom,” or “boam.”

Turning round and round, looking for something, an escape probably, deKlend notices a brilliant, tapering light, clear as a star, flickering like a torch, darting and twirling at the feet of the remote mountains. This incandescence flits along the ground in a kind of racing dance, tracing a shapeless character; it leaves no streak behind it, nor is it at all troubled or distorted, the air is so clear and still. It’s like some divine messenger, revelling in his exalted charge, and enjoying the sacred delay before he delivers.

Now it becomes distincter: the shouted word is Burn!... Burn! Turning around again, deKlend sees him, hurrying toward him down the short slope. He vanishes into the thick shadow of a boulder, so only the glint in his eyes can be seen, darting through the veil like a flashing needle. Velvetty hands emerge from the shadow and take up deKlend’s bare arm. They raise it, bent at the elbow, and the black, veiled mouth closes firmly on the fullest part of the forearm. There is no pain, only a sort of tugging, opening feeling and lightness, and as the arm is slightly lowered there is a bite taken out of it, like a bite in an apple, the clean, bloodless, fine-grained flesh and the crisp grooves. The veil has been broken by the teeth and driven down into the gaps between them, so that each tooth protrudes naked and as it were delineated by the veil, which folds into the mouth behind and around them. The toothed veil grins madly at him. The arm is raised for another bite when the figure stops, closing its open jaws, and points to a brown spot on the arm, like a soft discoloration on the skin of an apple.

Rotten! (he says flatly), his teeth opening and closing twice. He seizes deKlend by the neck and tosses him headlong over his shoulder. As he wakes, deKlend hears resumed again the sonorous call Burn!... Burn!... Burn! He is still crushed in the blazing lava and sitting on the cold, wet grit beneath the table, writing letters with the tangy smell of varnish in his nose.

In Votu:

Pilgrims to Votu come to worship at the shrines of the five natural robots.

the NATURAL ROBOTS:

These are robots no one built, which were formed spontaneously in the mountains. It is generally believed that they owe their being to a very unlikely succession of complications in the process of stalagmite formation. Metal laminae and minate crystals form where conditions permit natural electrolism to occur in the vicinity of magnetic veins. Travellers in the high mountains have remarked time out of mind on the plaguey static electricity they encounter, which made everyone’s hair stand on end and set everyone’s woolens crackling above a certain altitude. Batterized stones murmur to themselves all over the slopes. The natural robots are supposed to form when a particular concatenation of dry cells, minate armatures, silicon and crystal formations occur. Most of them are so simple as to be indistinguishable from any other sedimentary formation. The moving parts are microscopically small gears and springs, floating in jellified crude oil.

Naturally not everyone agrees with this version of events. Other, arguably wiser, persons leave the mystery of the origins of the natural robots alone.

The larger, more elaborate robots have always been worshipped, if not quite as gods. Many orders of mathetes have been established over time to attend to their maintenance, and because it made sense to dedicate a body of people exclusively to the task of studying them. The discovery of no end of new inventions has proceeded from close scrutiny of their workings and behavior.

It is forbidden to name the robots, so they are given only nicknames: there’s urchin, groper, troglodyte, anemone, and urn. Urchin looks like a sea urchin, a haystack of pipes around a two-part body, with a single hydraulic foot. Groper is a mechanical fabric and looks like a whitish-silver tarpaulin draped over a mammoth caterpillar that isn’t there; it is in constant motion and feels its way along with giant ‘hands’ of charged plasma. No one has ever seen troglodyte, who never leaves the cave below its shrine; it is all covered in a material so highly reflective that even the faintest light rebounds with blinding intensity from its skin. Anemone is capable of flight; it is a boxy turbine skirted with machine fibers and spherical jettiphers. Urn is actually more like a massive goblet with rough vertical stripes of rock along its sides, and huge drills.

It is not strictly forbidden to name them, after all, but the mystics of Votu do not name them, and maintain that the nicknames applied to them are the names of concepts that substitute, at a single remove at least, for the beings themselves.

Most people with an opinion believe they have no senses, nor any need of them, their instantaneous schematics of the world being so perfectly precise, with respect to the disposition of events ghosts and objects in time, as well as in space. It is more than probable that the mysticism of today is rooted in oracle cults, whose adherents could think of nothing better to do than to pursue a fleeting mirage of advantage by prising future secrets from the machines (or so they thought). Long dead Reverend Ti Yunzonor, who pertinaciously contemplated troglodyte, observed in his Night Whispers that mastery of anything always appears to the uninitiated as strikingly natural. “So-and-so makes it seem so natural,” people say. From this it follows that the more natural something is, the more of a technical accomplishment it is.

That the larger robots gathered in Votu might account for the foundation of the city in a place that has little else to recommend it (there is no river, for example), is suspected. History relates that a small group of persons, very likely nomads, were witness to the arrival of urchin, then known as burr, ‘walking’ on a single leg, very low to the ground. (It stands actually on its knee, pivoting the leg around from front to back to set down its snowshoe-like foot ahead of it, then it glides forward on that foot, drawing its leg up into a cavity, and therefore not rising much, until the heel is nearly past its rear; then it drops its weight forward onto its knee and repeats. Dances reputed to be the oldest in Votu reproduce this way of moving.)

Urchin stopped, legend has it, on the site of its current shrine. Other natural robots soon came into the vicinity in order to have sex with urchin, and it was then that the chemistry between them all was first noted.

Garsenόseo was the name of the first mnemosem to write anything enduring about the natural robots, but, since he is thought of as an uncouth and shaggy gymnosophist from the sticks, his work, despite its great antiquity, is not much respected and is studied, half-heartedly and in haste, for its age only. One of his aperçus, however, remains

unshaken in the commentaries. Waving his hand, vaguely indicating the world, the stars, and everything existing and happening in between, From the point of view of [the natural robots], all this is sex (he said). When asked whether or not he thought the natural robots had minds, it is said the question delighted him. Who knows wholly other instincts? (he asked) Do they eat?

One hundred and eight years later, Quil Qusogh (who is credited with discovering the chelating power of molasses, and promoting its use in preserving the natural robots from rust), wrote: Their purity consists in a neverending inner sexual intercourse, each within each, as well as with one another, and as well with all manner of other machines, which are of human origination, and not of their origination. Quil also was the first to refer to them as living mathematics.

There has never been a time when the natural robots did not fascinate people and provoke that mimetic reflex so particular to human beings. The mathetes devote themselves to the imitation of natural robots in all sorts of ways within the various orders, and account resourcefully for what they do. Readily they admit that they are projecting human affects onto beings that all but certainly don’t really have them, although there are those who like to speculate on the intriguing question: could the natural robots arrive at human affects in an entirely inhuman way? The spiritual work of the mathetes is a form of translation, according to Ti Colacόlashi. Serenity, for instance, is imputed to the robots and cultivated by the mathetes, but as a mimetic imitation only, which is to say they understand that they are mimicking what imitating the machines would be if they could be understood in human terms, which, it can’t be denied, it might be that they could. Some—especially the followers of Ti Uch Kazkerl, who are in bad odor with the other schools—advance the idea that human emulators must be prepared to replace the robots themselves in time, as purer expressions of the struggle to become natural robots themselves.

Votuvans pay tithes to maintain the shrines and visit them on Tennkee Yúvhanho, a term analogous to holiday, meaning Occasions of Special Efficacy.

Of course we still honor the natural robots (they say), with a slightly hasty, slightly embarrassed air, the way one might say, Naturally, we’re all good Catholics here...

There is a ‘but’ waiting in the wings.

deKlend:

Any country can become a ghost country. It may be brought on by too many people seeing their reflections in the dark in too brief a period of time. The place becomes deserted in the first hour before dawn, as the pallor begins to gather together. Many will return, stupefied, emerging from closets, from underneath beds, from basements and attics, from beneath bridges; it is clear that none exactly or simply die. They change; some instantly become other people in other parts of the world, or what could be taken by anyone as such, with ordinary memories filling their heads, and the recollection of any former life utterly vanished. As for the others—that street lamp, that tree dripping condensation, that trash can, that fountain, that bluish loaf of bread... It may be that some items will also disappear to turn up elsewhere, and one day you might meet your old long-lost kitchen cutting board walking up to you on two legs and asking you the time, showing off its new glinting eyebrows and white choppers. As you look up from your watch, he is smiling insanely at you, sawing gently at the back of its hand with a finger. One of the most far-reaching consequences of this phenomenon is that no one can ever know, having acknowledged that it happens, who they, or any other things, are, except perhaps just for the time being. The water glass on the sill of the bedroom window upstairs might just have become a stranger you’ve never seen before, from a suddenly empty town, on the other side of the world. Luckily these ghostly episodes are rare; no one has ever actually known one to occur in living memory.

deKlend passes through the haunted town. “5% Less Ghosts!” is painted on the wall of the L-shaped, empty brick hotel. Half the buildings are scaffolded. The hotel Bradblaine has a bronze plaque on it identifying it as former home of the local SPR. The green-walled downstairs room, a tall effete man with his hodge podge of a girl... the rooms are arranged railroadcar fashion so that deKlend has to pass through theirs to reach his own. She has many dogs and other animals, heaps of old furniture and trunks like the back of a junk store.

Sorry! Just go on through please! No, that way! That way!

Everything seems to fall into place, foreordained like already written. Nothing surprises deKlend about this place, although he has no idea what to expect. After checking in, deKlend walks out into the wide empty street and finds a drafty eatery, tables of young people sullenly drinking koumiss, a very high ceiling with bright, remote lights. A cynical, vituperative young man accosts deKlend, calls him something he can’t make out... You city types (he snarls)

deKlend is homeless, as any idiot can see. He isn’t dirty, he doesn’t smell, he isn’t penniless, but he is not exactly the city type.

There are bodies lying in rows of coffins under the loose floorboards. The insulting young man gets up and begins flipping the boards back to expose them, glancing up at deKlend every few moments. Then he reaches down and brandishes a “dead body” at deKlend—it’s actually a rubber prop of a flattened, naked dead man, skin pocked a bit like baked cheese, staring eyes, horrible crinkly hair.

The next morning, grey and nearly lightless, there is a frantic, if faint, knocking on the door of deKlend’s partition. The insulting young man, pale and trembling, is telling him that someone is asking for him—

There’s a whrounim out there. He says he wants to see you!

The whrounim stands in the middle of the street, only half emerging from a sapphirey cloud of fog. He is tall, urbane, silent, swathed in thick and abundant clothing, with a goblin face—pointed chin, pointed nose, pointed lips, pointed ears, pointed eyes, pointed brows. He’s got on a Homburg hat. As he approaches, deKlend thinks the stationary man’s face is the bluish color of ice, but as he gets a little too close, he sees that the whrounim’s face is speckled with all colors in tiny patches, each about the size of a pore.

So this is a whrounim (deKlend thinks, taking the note held out to him)

The whrounim leads him on with silent exultation, as though he were conveying deKlend to paradise. Whenever deKlend says anything to him, the whrounim, who walks a few paces ahead, stops, slowly turns in place, and stares at him in silence with a gloating smile. Eventually the whrounim turns back and resumes walking with the same hasteless deliberation.

As it nears the ground, the fog crumbles into snow.

Ahead, an archway looms a hundred feet high at least (deKlend mistakes). The arch is the opening of an imperceptibly-descending tunnel that bores down spaciously into the earth. This tunnel is scarcely less light and airy than what had come before, given its height. For all that it is long, there is never any real reduction of daylight and every inch of the pale brown cement walls is plain to see. The whrounim walks in front of him, tall and elastic, with a light dull footfall.

A few scarce snowflakes begin to fall around them as they reach the other end of the tunnel. Beyond there is a sky of brown, dropping with snow, stalklike winter trees, glistening black streets with no buildings. A vast plain, and the city entombed in the distance, palace temples, some lined in lights like bioluminescent jellies... a brass building with columns... ochre domes, dreamlike colors vivid if not quite bright. The lights of the carriage fasten on the gate of the school.

The Madrasa’s faculty are nearly all incredibly aged people—some of them, huge men with beards to their waists, robust drawn and liverspotted up to their eyelids, lumber obliviously around the campus in rags entirely ignoring the students and even the other teachers. In every corner it seems there’s a half-dematerializing old coot wheezing, hand held out to no one as if to say ‘wait, let me catch my breath’—the face turned away and dimming into the wall.

In the dingy atrium, there is a slab of peachy marble with a brass inlay outlining a woman’s face, the thick Mucha-like tendrils of her flying hair stream to

fill the rest of the space with sinuous curls. The face is almost circular, on a neck that bends like a stem in the same gust that blows her tresses aside, with large eyes the liquidity and gleam of which the artist has taken pains to represent, although not well. She has a rapt, zany expression, a prominent overbite, and complicated lips. A ragged, skeletal instructor, shambling across the atrium like a man reeling out of an explosion, informs him that this is the tomb of a rich window who had provided for the establishment of the school.

The instructor’s voice echoes strangely, not rebounding from the walls around them but just floating away in fragments, as if the drafts here repeat them to themselves. He leads deKlend through a doorway and into the halls, lit only by small round skylights. The interior of the building suggests a wasps’ nest laid out in accordance with strictly functional institutional design. The instructor stands by a door and gestures him into a chilly classroom with cork tile ceiling. He’s gone when deKlend turns around. Deciding to wait, deKlend seats himself on the frosty floor at the back of the room. He adjusts his muffler, the shawl swathed around his shoulders, and the pair of blankets he wears like a robe, secured about his waist with a leather belt. There are chalkboards on two walls, a blank wall, and one with windows, a flag drooping on a pole, some coat pegs on the blank wall, and a wire wastebasket. Otherwise the room is entirely empty.

Celebrant

Celebrant