- Home

- Cisco, Michael

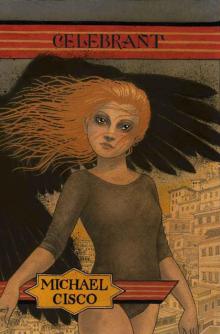

Celebrant Page 17

Celebrant Read online

Page 17

Out a window, the moon half-rubbed from the void by a smoky cloud. The sky still blue even at this late hour. A red ambulance from the fire department idling in the street below. Its yellowish headlights are weak as if the battery were going.

I have (deKlend thinks) a familiar feeling of unreal—unreal something, unrealness. I’m sleepy and a little disoriented. Just the combination of the moon, the close, feverish air of the day. Good (he thinks), I think—smoking moon... gelatinousnight, the remote factory and railyard sounds, and muttering, like a huge crowd somewhere. A radio playing the official broken record.

This is not a moment that’s going to lead to anything; it’s just a moment aside.

The word ‘restaur’ can be seen, on a bulge in a loosely-rebundled newspaper there on the nightstand.

When I was a boy (he thinks irrelevantly) I would assume that ‘opening a restaurant’ meant you started from nothing. A stereotypical children’s drawing of green grass, which I expect children draw because they know they’re expected to, a tree, the blue sky and sun, building the restaurant all by yourself, building the building, installing the stove and equipment. If something went wrong, say, with the boiler, the waiter or the chefs, who live in the restaurant like sailors on a ship, would be there to deal with this problem. And even if my mistake is explained to me, I would (he thinks) go on sulkily insisting that a restaurant of any other kind than the sort I’d imagined, built from the ground up by the proprietor, would be somehow inferior or false to the one I imagined.

Had that been his initiation? When, as a boy, he had been suddenly overwhelmed by the luminosity of the air, the distant town trailing the road like a dropped tether, the equally distant ocean, the grassy undulation of the land falling away on all sides, seething and whispering, so that he collapsed at the roadside in tears, in a posture of abjection, staring ahead bewildered, adoring, distressed, so that, to turn his head and see and hear a bird clinging to the branch of a shrub, and then to turn his head the other way and see the blaze of sunshine on the nodding, plain little flowers was to heap enormities on enormities, like world-sized crescendos upwelling from some implacability somewhere of ordinary beauty, awful, dignified, real.

But then I wasn’t a still boy (he thinks in surprise)—still a boy I mean—I was fourteen! Imagine being capable of that at fourteen, when I had already assumed my masculine temper!

Ah, but then isn’t it that way (he thinks he thinks philosophically) generally? Perhaps the very effort with which I laid into the task of steeling myself to manhood had overtaxed me, and I snapped, falling back into childish weakness.

When he saw Votu, though the buildings were very beautiful they didn’t strike him half so forcefully as the people, who seemed ordinary and yet were extraordinarily beautiful—was there something different about them or about him when he saw them? Were they special people, or was it that his way of seeing them was special, just then?

deKlend draws air deep into his lungs through his moustache and billows out his misshapen sword blade, taking it gently in his hands he sits up on the edge of the bed and turns the blade over and over.

This is the misbegotten image of my self-discipline (he thinks, with a not unpleasant ruefulness). Flawed by overworking. Yes, each flaw worked carefully in. I started work on it entirely too early. But (he sighs) I can’t dispense with it now, any more than I can with myself now. It’s all too late. And I have to redeem all that effort somehow.

With heated fingers he begins to smooth the edges of the blade carefully. Gradually the warps begin to dwindle.

A flambeaux (he thinks with excitement) I’ll accentuate the waves, and make them regular!

As loyal to me (he thinks as he works) as my death—there is nothing so faithful to me. All my long life long, my death will never betray me, my death will never abandon me, it will keep its promise to me. People can’t keep their promises; it doesn’t seem as if they can. This realization makes me feel compassion (he thinks) or maybe it’s affection, for them. They can’t help it, I can’t, breaking promises. Death is a hero (he thinks) because it couldn’t keep its promises any more perfectly, but knowing that doesn’t amount to knowing what death is—death’s loyalty is never a feeling: if death could feel the faith it keeps, it couldn’t keep it so perfectly. Death just says, voicelessly: you can count on me. What more reliance do I need?

Shaman relies on death, rightly or wrongly. But there’s more to it than that. Shaman may also make promises to death. What about that?

I make promises to my own death. Always only parts of the answer, or you want (deKlend thinks) to say that, but what you mean is no complete answers, only partial ones. You don’t (he thinks) want to claim, I don’t think, that there is some total answer coming together somewhere. You can produce wisdom, and speak like a prophet, but you should understand when you do this that you’re improvising in a moment and that these words may turn out to be the least portable, and can’t leave their very special moment without instantly being pulled inside out. Like the so-called student of magic? No such thing.

There’s no conscious plan against magic (he thinks) It simply can’t abide where mediocrity is. And ‘the whole world’ is a mediocrity, and more and more so all the time.

And there’s no way to study it?

Remember library books, when you were young? Mysteries of the Occult? True Magic? Do you remember walking down Waltonia Street, reading that book about talismans, and a bird in a tree shat on the page as you went below? That bird had the right idea. Read a book about magic and you will learn about magic. You will learn what people thought it was, what people (he thinks) historically had to say about it. A historian of magic is not for that reason magical. So magic is another word for excellence no, it’s just another word, period. I don’t know what that means (he thinks).

It’s what you do when what you do can’t be explained, it is the art of doing something you can’t explain and if it were something that people could learn or understand merely by having it explained to them then we would all be Merlins and actually (he thinks) magic is still magic even when ‘explained’ because the explanation won’t take, won’t work, isn’t afraid of explanations, without resisting, so you still don’t believe it. Believe which? Never mind, what is true is that training is paying court to chance, like knowing something about luck, but only like that, since there’s nothing actually to know.

Now (he thinks),

taking his sword abruptly back into his lungs. deKlend gets up and begins piling the furniture on the bed, including the heavy bureau and the desk, and pulling up the carpet to reveal the naked floorboards,

the purpose of the ritual is not to minimize chance, take care of every little thing. To minimize chance in the archery ritual (huff) you need only walk up to within a foot of the target (puff) shoot, and leave. By adding ritual measures, one is actually working to increase to the maximum the number of things that can go wrong. A step out of time, or the wrong (huff) length, or too many or too few, or one of the archers, (puff) in baring his right arm, gets it tangled in his sleeve, or someone sneezes during the one and only shot he is permitted. With all these additional opportunities for things to go wrong, the final success which caps the (no, put it there) ritual must be an act of fate, not of human skill or at least not as ordinarily understood, it must be a kind of blessing, an image of order—one watches the ritual breathlessly because one is carefully looking for any mistakes—status is idiot magic—if you would be happier not being an idiot, follow me, now who said that?

He turns on the radio and writes the letters on the floor to the rhythm, a small paint can in his left hand against his chest, brush in his right. Standing upright, he bows to write a letter, comes up, and bows again, writing the next. The letters are hastily formed, thready and spotty. He has only time enough to dip his brush once, without looking, between beats, and it comes out dripping from the can. He sneaks into a tall paper tube in the middle of the floor and, after a momentary pause to recover

the beat, he begins covering the interior of the tube with letters. Loud speech in the next room coincides exactly with his writing. The tube wobbles as his brush taps it. A draught strong as a gust of wind blows across the room, the cracked and peeling letters on the floor split apart and scatter in flakes from letters of trembling fluid gold. Inside the tube, there is a throne-like chair with waffled cushions of coral-red velvet, the back is tall, narrow, and stiff, with two carved tufts sticking up, and the arms are thick whorled rods like drill bits worn smooth. My shadow sits in the chair with its head dropped forward and its arms on the chair’s arms, and I wake up in the futuristic cafe car of a bullet train. Brilliant white, the windows are huge, dimmed with blue-grey pigment, with rounded corners and thick white rubber collars. Through the window I can see the city lying on the water and, on this bank, we are so high in the air that I can see the skyscrapers on this side only by standing right in front of the window looking down. The daylight outside is dazzling and suddenly vanishes; the sky turns black ablaze with stars. But the city the water the skyscrapers glare brighter than ever in sunlight that seems trapped beneath the sky—daylight returns the next moment still brighter—then again the sky turns black, while the land flares so that even through the tinted glass my smarting, tearing eyes can actually see the broad flat beams of diaphanous light rebound from the buildings. The sky blackens, and bursts back into full illumination again and again each time that blackness comes with a silent but palpable sensation of a rolling thud, and it seems to me that the dark sky is a limpid black jewel that crashes down, malloting the city and the land beneath it, flattening them, and it’s these blows that compress and intensify the tenacious daylight.

The city is gone, the sky is a dim even bleached blue, I am looking out from a stationary train window at heaps of mid-sized dark stones the size of human heads, seamy and nuggety like lumps of scrap iron, and the ocean, flat and sheeted to the horizon with foam, knocking at the door. There is knocking at the door again.

Come in (he calls)

A lovely young lady comes into the room looking irritable and a little fatigued. She is wearing what resembles a conductor’s uniform of smart dark grey twill, a snug skirt down past her knees, high socks of thick black wool, and shiny, durable-looking walking shoes. Her tunic has metal buttons like steel mushrooms, and a boxy leather satchel hangs from a slender band across her body. Her collar stands up like a cadet’s, and, from her kepi, with its short, polished visor, blue-black hair cascades down to the small of her back and over her shoulders to the elbow. She comes up to the bed, where deKlend lies at full length on top of the covers with his hands folded over his abdomen. A trace or two of make-up still remains on her face.

In a beautifully accented voice, she asks him his name and he answers.

She briskly nods once, exhaling audibly through her nose, and, putting out her hand, demands his invitation.

Invitation? (he asks) Just a moment...

He lies there without moving. Her hand remains in the air where it is.

Paper? (he asks)

She compresses her lips and, drawing up a little straighter, opens her satchel, pulls out a blank piece of white card and hands it to him.

deKlend takes it and flips it over in front of his face, still lying down.

Perfect! (he says with a smile)

After a moment or two he selects the better of the two sides, stroking it once gently with his fingertips.

Have you got a pen on you? (he asks, without looking up)

He hears a sigh, and now a pen is thrust before his face. He takes it and, resting it against his drawn-up knee, begins to fill it out. He draws a margin all around the interior of the card, both to fill up space and to buy himself a little composition time. The line is very thin. The attendance of deKlend (he writes—no forgetting to write his name this time!) at the Belvedere (it is the name on the label of his jacket) on the evening of the thirteenth of this month (yesterday, a bad choice made in haste but a crossing-out looks worse) is civilly requested for symposium. Refreshments will be served (can’t be too careful about that). No RSVP expected. Flowers appreciated. Sincerely, Mnemosems.

deKlend waves the card to dry the ink, but her hand snatches it impatiently from him after a moment. She tells him the envelope will be provided. The hand reappears before his eyes.

He looks up at her face, foreshortened above her chin, and awe steals over him. She opens and closes her extended hand rapidly, with a dry brushing sound. Abruptly recalled to himself, deKlend remembers her pen, which is a fountain pen. Hurrying to oblige her—with a fear of her displeasure that swiftly grows more acute—deKlend tries to close the pen. Holding it in his right hand, he aims its tip at the cap he holds in the fingers of his left hand, and misses. The sharp nib jabs his finger, and a bead of dark blood wells out as he withdraws it suddenly the nib is inside the cap and he is twirling it shut. His finger is not injured. This was no trick of the eye. It happens in an instant. Just before it would have touched his skin, the pen blinked sideways, passing clear through the side of the cap, and magically into place.

In Votu:

In Votu, people believe that there are two moons, one light and one dark, and the regular changes observed from earth are the phases of the sexual intercourse of these two satellites. The new moon is the time of the most perfect satisfaction, the complete and thankfully temporary evacuation of all desire. The full moon brings on insanity because it is just the opposite, desire heated to blue-white heat, for which there is no relief. When the moon is full, lovers can’t get enough of each other, no matter how long they love each other it’s never enough. The howling of single people rises into the sky from every quarter. And those whose love goes unrequited go into convulsions—there’s no question of masturbation or of seeking out substitutes. The frail unrequited must drug themselves into insensibility or risk death on these nights, and some men have been known to castrate themselves in the desperation of acutest despair—especially when they know the one they love sports in that same night in the arms of someone else.

The sun rises in the rain, and the rain goes on all day. Pigeon girls with no place to shelter huddle on roof tops with their heads down and arms around knees, cold rain spattering from their saturated hair and clothes. Here they have taken shelter—thankfully there is no wind—each in a different window of a five story brick building. The people working inside tolerate them there, and they fill the wall, with its bright awnings, like saints in niches. Bedraggled rabbit girls creep into basements, barrels and boxes, unable to use their now-flooded drainpipes, or scoot hastily from cover to cover, teeth first. Even under these demoralizing circumstances desire, not sexual, not unsexual, something nearly but not yet sexual, frisks in their bodies, just growing body desire.

Burn had wandered out by the tumbling houses, which turn continuously like huge dice. She walks with her hands behind her back.

A boy looks up from his howdah-like stroller, his mother under a domed umbrella, and asks

Who’s that?

—as if he were entitled to know who she is, and as if his mother would recognize her. His mother takes no notice and wheels him away, but he goes on staring at this pigeon girl in her soaking wet, icy tardoleo, her hair lank and dripping. Burn flicks up a wall to perch in the inner corner of an awning, where she can keep herself precariously balanced.

Below her, through a shop window, she can see a row of seats, and there’s a little girl, slightly younger than herself, and plainly not an orphan wastrel, sitting in one. The little girl is slapping the arm rest of her seat and singing out an improvisation on the word outch, playing with the pain in ascending notes.

Outch, outch, outch, outch...

By the time night falls, the sky is clear and the city is fresh, all the colors deepened and vivified by the rain. The sunset and twilight are rapturously beautiful, clouds bounding away like violet gazelles and the sky singing out its changes.

The full moon festival begins tonight. There i

s a festival for the new moon as well—three meditative nights of quiet drone music, the slowest and smallest dancing, of the most refined and simple enjoyments. The full moon festival is just the opposite.

The music begins to break forth as the moon soars clear of the mountains. It has mountains of its own, and they can be distinctly seen, the rain has scrubbed the air. An exaltation of passion begins to churn around the city.

Kunty has found Gina, resting quietly in a warm corner of the back of a gardening shed no one uses. Gina, who is naked, hears Kunty’s claws on the wooden planks of the floor and sits up calmly, resting on a big burlap sack of potting soil. Kunty, still saturated with rain, comes toward her, breathing hoarsely, the full moon at the window in both of her eyes. She is standing upright. Now she yanks her dress up over her head and throws it angrily into a corner, dropping as she does so onto all fours and returning her glowing stare to Gina’s face. Gina observes all this with her usual serenity, perhaps a modicum of curiosity.

Kunty is scraping up splinters with her claws, staring at Gina and panting. Gina can see well in the dark, and can make out easily the two bare legs folded to either side of the body, each thigh crossed with a deep trough along the muscle, each rib, the groove along the shoulder. Also the slack, fascinated mouth. Her hearing isn’t so sharp, so she can only just make out the very faint sounds, like the faint creaks and whistles that come from an unoiled hinge as the door is tugged to and fro by an imperceptible draft, that escape Kunty’s throat.

Suddenly Kunty stands up again, takes two steps, and throws herself down onto Gina, writhing against her, whining, gibbering, rubbing her face over Gina’s cool skin. Using the tips of her fingers, not the nails, she runs her hands all over Gina’s back. Kunty stops, her attention riveted on Gina’s left breast. She latches onto it with her lips, breath in her nostrils and her eyes shut hard. Gina passively lies where Kunty pushed her. Absently, she raises her left hand and rests it very gently on the back of Kunty’s head.

Celebrant

Celebrant