- Home

- Cisco, Michael

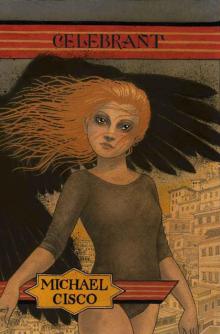

Celebrant Page 14

Celebrant Read online

Page 14

deKlend woozily resumes his work and this time a slow but implacably building mania battens on him. The furnace’s feather boas whip all around—he can be seen bounding in the flames as he strikes the iron first with one hammer, then the other, then leaps up on the anvil to stamp it with both his heels. The building sways and the gaps between the boards flutter, the planks are starting to smoulder, the wood smokes and chars with the heat as days and nights sail by in a blur, and now the whole building is thickly plastered with red fires that burst like viscous sweat from the groaning wood, the timbers clash, the boards tumble down on top of him and are burned. Now, scorched from head to foot, blasted by fire, surrounded by the charred shed, in columns of smoke and charcoalized stalagmites, the furnace like a ruptured clam beside him, his hammers vaporized, deKlend holds the red iron in his hands and whacks it crazily against the anvil. The hammerheads seem to have been driven into the long, pointless shank, still with a surly inflammated redness under its quickly blackening skin. He lifts it up, almost as if he proposed to swallow it, too, but he is only raising it to look judiciously down its winding length.

He raises it, as it happens, to that point precisely where the sun is on the high horizon, on top of the mountains, so that it seems to touch the sun like the tip of a key brushing the keyhole. A sort of crispening sensation goes down the blade, and, with very gentle pressure, deKlend uses the sword to split the infinitely thin divide separating night and day, then turns the shank with a sharp twist.

Black night glides across the sky, ablaze with stars, then the next instant the sun bursts directly before him in a dazzling eruption of light, the next instant is night—an icy splash in the face—then day—stunning conflagration—night and day pivot across the sky in alternation faster and faster until he sees both the sun and the stars at once, the earth far below his feet firmly planted on void, and stars like half-melted snowflakes hovering motionless in between—day and night at once, seen from the right distance. Getting up, now in the daylight only, from where he had been lying on his back, deKlend looks numbly at his outline in the long wet grass, the dull, lead-colored, bulging and misshapen sword blade still clutched painfully in his hands, stiff with cold.

Adrian Slunj:

Everything seems too vivid—the flowers—my celibacy—the brilliant spring day—heavy interference. Brilliant interference—traffic and street sounds rage and claw at the air. Pungent, unaccountable smell of turpentine, must keep windows open thus admitting noise. Loud shrill conversation under window. Look at a solitary, small cloud in the bare sky, brilliant and soft—defilement energy needs purity, like a brilliant spring day, this cloud, the songs of birds, soft air in dark green branches, to profane.

Stepped out to get a little milk, people laughing like maniacs near me but not at me, at least not apparently. Their gestures are abrupt big and invasive; yes he’s too expanded by the exaltation of the day and his own thoughts and from their point of view this is only a vulnerability. Their words and gestures slash at a spirit balloon inflated around him. The store I plunge precipitately into is wrong and I know at once I shouldn’t have come in. I’m too exposed to something tainting coming from the air conditioning, the music, the writing and drawing on the cellophane packages. Return to the room. The gust of wind billows curtains across the room, but I can feel nothing. The air in the back of the room is too dense to be moved. Noise raging on the wind, claws at the spell of the book he is trying to read, so that I experience the sirens in the street in the style of the book. I notice his moment to moment experience is styling itself after the book in his hands—a hypnosis, the voice, that which the noise outside is doing all it can to drown out and destroy—IT can’t tolerate that hypnosis.

What is IT? IT is what wants him in ITS hypnotic sirens—preoccupied, nervous, worried, afraid, alarmed, rushing, enumerating, frustrated, stupid, excited about a sale, the siren has no use for solitary small cloud.

Adrian is cutting little people out of paper. The paper is thick, and makes a loud harsh noise as he cuts it. He paints each one from a watercolor set, all in cadet jackets and cloth caps.

*

Adrian surveys the wall, which extends a considerable distance without any gateway in either direction. Then he produces his triangle, holds it up by the cord, and strikes it once at the midpoint of the base.

Students! (he cries through teeth locked in a ghastly smile)

At once a platoon of students comes stamping out of the fog and gathers at attention around him. They all wear cadet jackets and cloth caps.

Adrian gestures toward the wall. The students bustle over to the wall with a sound like barrel-fulls of old shoes being emptied down a long staircase. With hup! hup! they form a human step ladder, and Adrian strides up their bent backs to the top of the wall. Here he stands, erect against the sky, waiting. The uppermost students climb onto the wall and help the others up in waves, spilling down the other side, climbing up or down their hanging bodies.

As the pyramid reforms on the opposite side of the wall, Adrian waits, arms folded pensively behind his back.

One must maintain purity in body (he thinks)

The tickle in the throat—that is not what causes the cough. Coughing is a spasm of the diaphragm, which can be controlled. When I have the impulse to cough, I redirect my attention from my throat to my diaphragm, and compel it to relax.

And hiccoughs?

He is about to ask himself that, even to the point of self-consciously selecting the old-fashioned spelling, but stops himself. It seems the right form of control, to control the question.

He has a way of singing with the mouth firmly closed, and suddenly says, in an unctuous tone, “every impediment under the sun,” as if he were bragging about the selection in his store.

As he waits for the pyramid to form, he sees in the distance a few poisonous birds, dancing albatrosses billing on the rocks even though the ocean is nowhere near. And above the meadows, in the gloom under blackening clouds, dangerous, locustlike flocks seethe. The split tail and wings of the raven like fountain pens, feed on dead soldiers. It is clear the street was putrid, the impasse drives all things.

And if it weren’t for him (he thinks) for his terrible avian charisma, I would still be back there, helplessly watching the future come. All the poetry going out of my desire, starting even to avoid it assiduously.

His words come back now, as if someone stands behind him and speaks them—

Life can take any shape, death included, my non-son (it says)

Slunj: Oh, what an earnest slave and noble master am I. My running over is cupped. Sniffs dart to and fro across the theatre. The quality of straining is not merciful, the mercifulness of strain is not quality. The stinking narcissus—

The pyramid is ready, and he descends it majestically, holding himself as straight as a puppet on a string, as always.

—the stink hour of the narcissus (he thinks)

*

As a young boy he began, of his own volition, to keep notebooks for the purpose of self-improvement, and around this time he began to distinguish himself from other children by a preference for uncomfortably formal dress. He was airily censorious, holy, a solemn liar and full of bad conscience. His English tutor described him:

Adrian is a kind of half-born soul whose life is an escrow of axiomatic reasoning about life and the drawing up of plans which will be carried all the way through by the impetus of sheer severity with himself. So his every encounter must negotiate its way to him through a maze of absolute ideas that is undergoing perennial refinement. Nothing reaches him without adopting the protocol, and so he is always too early and too late, and there is nothing necessarily relating him, in his deliberating spot, to life, apart from his own relentless insistence on having his way... Even ordinary tasks represent for Adrian a series of trials and sacrifices which, I believe, give him pain he forbids himself to display. It seems to me he does this in order not to make inappropriate claims to the sympathy of others, and to av

oid any effort to appear special... He has a talent for comprehensive planning that he brings to bear on petty thefts.

Adrian had been afflicted with tongue thrush when he was a baby and never outgrew it, so concealing it is second nature to him. Early on he learned to speak without separating his teeth, opening his jaws only to set them edge to edge; his lips, which are beautifully shaped, writhe across his perfect teeth, bottle green in their transparent parts, like skaters over the ice. He shrinks from the faintest trace of sourness or astringency; he likes insipid food served cold, and thinks of himself as naturally abstemious. Since tongue thrush thrives in alkali conditions, his diet encourages it. His breath is so yeasty and malty it has you looking around wondering if there’s a brewery somewhere nearby.

Still young, his sharp, pointilistically-colored goblin face is presentable and would be appealing if it weren’t for the expression of gloating, secret superiority it habitually wears. He ambushes women he barely knows with abrupt declarations of weird, idolatrous love, often accompanied by poetry in English, as he has decided to distinguish himself—in letters—as he puts it. He keeps count of every one that rejected him and thinks of them by number.

Four was like death (he thinks) The viciousness of Four will not be forgotten. It will be remembered.

There were times he thought he would go mad with sheer misery, looking on to his impossibly distant idol, and fling himself down on the floor feeling like a damned soul. The idea that rejection and isolation should descend with such injustice on a soul that had so distinguished itself above the level of the common herd by an exhaustively-sustained awareness of its own unworthiness sharpened his anguish until he cried passages from the Old Testament aloud.

An affair of the heart—number Eight—was the cause of his wayfaring. In her case, he had been under the impression that she had set him a few qualifying trials, which he undertook and overcame with perfect obedience, great difficulties, and without a word to her, since he was required to prove also that he could respond to her unspoken commands and could uphold the entirely tacit regulations which forbade him to draw any attention to his successes prematurely—before all was finished.

When at last he found himself alone with her, in the small drawing room, by the windows, he started making astonishing announcements. Presently she overcomes her incredulity, sees his arduously far-fetched mistakes, and, repeating and rephrasing herself, eventually sets things in their proper light.

But you said...

His face is changing, and what for a split second she took for a sob, is giggling.

...But you said! (he shrieks)

Aghast, she freezes.

The room around her grows dark, but he brightens. For the first time his mouth opens wide, cackling. His eyes go round and glassy, his hair stands on end, his smile widens, cackling devours his face, his smile widens and distorts, spreading and distorting in freakish gaiety, his cackling increases and in the darkness his face seems to flash all over the room like firecrackers—but you said! but you said!—he is the room, the dark, the cackling.

Come back!

his laughter roars behind her as she escapes in horror—

I understand!

Come back! (the room howls)

timesermon:

Losing what my younger self, safely shielded by the favoritism of the past, gets to keep forever, the bastard—or at least until we lose it all; but even then that prick in the photos of me gets to keep what I have taken from me, or why should I take them from me? Is this the depredation of a future self on me? Is he going to call me prick and bastard? And do I have meekly to submit to his insults, even if they do belong to a closed econome? But time comes in from the outside to collect taxes and levy fines even. Fining me! Time is just a low-down impersonal unfeeling finer, and part-time tax collector, not even full time, since nobody seems to get full time. A full timer would occupy only a ceremonial post meant to address people’s expectations and maintain the fiction of time in full measures, but every unit of time is doctored and irregular from seconds to centuries, sex flashes by and the wait in between yawns the duration of a generation of sphinxes. Ageing part of incessant mean chiselling of time.

The boughs rise and fall like the breast of a sleeper, a soft gentle stupid seeking movement.

If we do not exaggerate. Then. Then when aren’t we slaves, to be slaves? When aren’t we reasoning, when do we ever reason enough by getting through enough of the doors and yards and parks, scenic walks, preserves, out to reason in the wild, still always at the doorstep—a cursed doorstep like a footprint, timepiece. Same old sleip. The scholar gypsy, who left the university to learn charlatanry, true charlatanry from the gypsies who taught him to read minds and slay demons like the diamond sword of the wayfaring Chinese scholars. He learned to leave, and was lief to have left his baffled friends where they found him.

Sleiping, wicked young man, an apologetically vile and ingratiating insidi, who wastes no time, not ever a moment; no matter what he’s doing, the insidi is wayfaring toward his immortality. Long life? So find what makes life long: boredom. I seek it out and repeat it, and as long as I am bored, patient, and waiting, the moments of my life telescope out in empty, tapering segments, to the horizon, in all directions. Fail, by all means, my boy, it’s good for you. A patriot must at times will the defeat of his nation. The partisan wants a tough resourceful honorable and noble enemy, a worthy opponent. Since when is time such a worthy opponent, when he sneakthieves everything by pinches and small measures and undermines—with no patience, don’t be taken in by that old line, time is as impatient as the next of them, but weak, so weak it can only pluck at you steadily until finally you drop out of tune, fray, break, are replaced.

If time were patient, I wouldn’t have to be. Time’s impatience is what compels me, or no let me say obliges me, if only because it’s niecer. Time’s impatience I evade—deft patience, with the same.

Time’s ingratitude, well, I don’t let that bother me all that much. It reflects more on time than on yours sincerely, because it’s neicer. I meet time’s impateince with my own particular and special sleip. Fresh kills, sirens go again—“I don’t like this part.” The police, and the working stiff, are impatient. They go through maybe one door, maybe one impateint time. In the time it takes me to spaek a single word they are alraedy exhausted. People simply take entirely too long. You should have called from another time zone. You ought to have been born dead, the laest you could do is live apologizing for the inconvenience you are. Still originally sinning and still living day to day with god kings everyoen insists are anachronisms, even if they do kill to their satisfeaction.

Obviously, you’re not supposed to exist, but these things happen sometimes, no one knows why, no one’s really to blame. We’d prefer it if you killed yourself but it would not be unsatisfactory if you would simply act as if you didn’t exist, keep out of hour way, go quietly into natural death when it comes. Yes, you’re very accomplished, not so bad looking, even witty and I daresay even charming, even erudite in your way. And so on. But, while we acknowledge all of this, as you’ve no doubt noticed by now, there is not the slightest conceivable use for you, anywhere. The feeling that one is at risk of being overlooked by the whole world that compels you to remind the world that you are still here in the room—what is the thing I’m supposed to be stubbornly refusing to concede?

Time will never be patient or grateful. A good thing too, because time is a tracherous friend and inconstant allie. ‘You must,’ time say, but what time must is another matter. And you have no say in that. You don’t get to tell time off. Sleip through time in patience and let it miss you, you won’t be missed. Time is too impatience and depends on your turning up again in the course of the churning, but this is not actually strictly assured and one can take advantage of time’s not really caring to keep track—that “careful record keeping” bit with the quill pen and logbook on the nineteenth century Dickensian high desk is just public relations. All sorts o

f business, all manner of contrabund—the coelocunt, for example—get by.

In Votu:

Ester presented it to her with high hopes.

Fuck chocolate (Kunty says) Let’s give it to Beaula.

Putting the chocolate inside her top, which is snug enough to hold it against her sternum, Kunty bounds away, with Ester close behind, to a spot where elaborately-carved marble bacheducts come within leaping distance of the ground. Instead of electricity, Votu runs on bachelorization energy generated in the city factory and circulated around the city through a separate system of bacheducts, thick marble tubes filled with heavy water.

They climb on top of the bacheduct and Kunty pulls back the heavy bronze lid with a grunt, exposing the trembling, perfectly transparent liquid and an almost pungently clean smell. Kunty waves the chocolate a couple of times over the opening and squats by it to wait. She repeats the gesture a few times and, after about ten minutes, a transparent naked rippling teenaged girl just appears there in the water like a vision.

Born very prematurely and tossed down a drain and somehow ended up in the heavy water system and grew strangely in the bachelorization energy she became the strangest of all the strange girls of Votu. About sixteen now, she is a water breather with cartilage bones and long toes and fingers tipped with conical nails, something like a sea anemone or a flower calyx that coils and uncoils in her groin, and long feelers in her hair and sprouting from her neck. Her Jewish nose divides in two sails with gill vents and her bulging eyes have crescent pupils giving her a weird, perennially bemused expression. Patterns pulse through her skin and eyes and long rubbery hair, even along her tongue when she speaks. Even her teeth change, each one like a tiny little television nestled between beadlike ink sacs in her gums. Cuttlefish girl learned language by eavesdropping through the viaducts and named herself Beaula; she speaks by driving water over her vocal chords. She never leaves the ducts, and has eluded capture both by virtue of speed and camouflage and because all her excretions come out sealed in satchels of clotted mucus she can toss from the hatches so she doesn’t foul the water, and hence becomes harder to trace and less onerous a presence to those who might try.

Celebrant

Celebrant